OVERVIEW OF REPORT

The 21st century has been marked by a series of overlapping crises, from the climate emergency and biodiversity loss to soaring debt levels, escalating inflation rates, and deepening inequality and poverty—all with severe consequences for the rights of women, girls and gender-diverse people. Women and gender-diverse people face disproportionate consequences of neoliberalism and its manifestations in austerity, debt, and an unequal trade regime. In the face of this “polycrisis,” feminist and peoples’ movements are challenging the unrestrained pursuit of profit and economic growth, championing a radical vision for economic and environmental justice.

This report highlights the significant gap between the contemporary global order and the vision put forward by the Feminist Action Nexus and our allies. To begin to determine how far away we are from this vision—and therefore how to begin to achieve it—this report assesses progress and challenges in seven key areas, corresponding to our key demands. As the first in a forthcoming annual series, this report provides a snapshot of recent trends, particularly from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 onwards. Emphasizing the agency of people and communities, this report spotlights both local sites of struggle against the consequences of neoliberalism and global advocacy proposals from civil society and Global South countries to transform our economic system.

THIS IS THE READ MORE

Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Donec dui odio, condimentum non venenatis vitae, consectetur nec eros. Fusce a magna feugiat[1] massa scelerisque gravida. Phasellus scelerisque sodales neque sit amet tincidunt. Curabitur convallis mi eu nibh finibus faucibus. Praesent semper vel augue at euismod.

[1] Fourth footnote

WHO WE ARE

The Feminist Action Nexus for Economic and Climate Justice coordinates collective advocacy and knowledge-sharing to promote the necessary transformation away from the fossil-fuel capitalism, neoliberalism, patriarchy and white supremacy that drive both the climate crisis and rampant inequality. The initiative aims to urgently and radically transform our approach to economic growth, our systems of production and consumption, and the rules that govern our macroeconomic and multilateral systems.

The conceptual framing for the Action Nexus is grounded in three key resources published in 2021:

- A Blueprint for Feminist Economic Justice, authored by Diyana Yahaya [English, French, Spanish, Arabic forthcoming]

- A Brief on a Feminist Decolonial Global Green New Deal, authored by Bhumika Muchhala [English, French, Spanish, Arabic forthcoming]

- A Brief on Human Rights & the Private Sector, authored by Sanam Amin [English, French, Spanish, Arabic forthcoming]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report was written by Shared Planet, led by Arimbi Wahono with contributions by Joanna Grylli.

The drafting process benefitted from review and inputs by a broad range of feminist intellectuals, reflecting the collective spirit of both the project and the analysis from which it draws. These include: Âurea Mouzinho, Bhumika Muchhala, Carola Mejía, Diyana Yahaya, Emilia Reyes, Friederike Strub, Imali Ngusale, Polina Girshova, and Sanam Amin.

The report was coordinated by Katie Tobin of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO), with inputs from Tara Daniel, Lindsay Bigda, and Bridget Burns.

The full report is available in four languages: Arabic, French, English and Spanish.

Design by Brevity and Wit. Web platform by Social Ink.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AfCFTA | African Continental Free Trade Area |

| BEPS | Base Erosion and Profit-Shifting |

| BWIs | Bretton Woods Institutions |

| CPTPP | Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership |

| DAC | Development Assistance Committee |

| DSSI | Debt Service Suspension Initiative |

| FfD | Financing for Development |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| ICIT | Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec |

| IIA | International investment agreement |

| ICMA | International Capital Market Association |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| ICRICT | Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation |

| ISDS | Investor-state dispute settlement |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IPEF | Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity |

| IPR | Intellectual property rights |

| LDC | Least developed country |

| MNC | Multinational corporation |

| MoU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| NCQG | New collective quantified goal |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| PPP | Public-private partnership |

| RST | Resilience and Sustainability Trust |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SDRs | Special Drawing Rights |

| SIDS | Small island developing states |

| TRIPS | Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights |

| UNCTAD | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| UNODC | United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime |

| VAT | Value-added tax |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

To achieve a feminist vision for economic and climate justice, there is a clear need to shift away from our unsustainable models of consumption and resource extraction. Yet, the world’s wealthiest countries and highest income-earners continue to bring in vast profits from fossil fuels, while neglecting to provide development finance according to their obligations and without which Global South countries will find it difficult to achieve sustainable development and climate justice. At current trends of income inequality, women will only achieve gender parity in labor income by 2100.

The proportion of low-income countries at high risk of or in debt distress has skyrocketed; countries are spending ever greater proportions of government revenue on external debt service—far more than on education and health, even at the height of the pandemic. The international response is largely centered around the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments established in November 2020, but civil society activists and Southern governments have condemned the Common Framework for its failure to advance debt cancellation, its limited scope, and for forcing countries to take on IMF programs to access debt treatment.

Tax abuse remains rampant, with hundreds of billions lost per year due to tax evasion by corporations and wealthy individuals. For low-income countries, this loss amounts to nearly half of their public health budgets. Countries remain pressured to keep corporate tax rates low, continuing a decades-long trend, while making up the revenue loss through higher consumption taxes which unduly burden low-earners over the wealthy—often at the direction of institutions like the IMF. The OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting coming into effect in 2024 fails to address the scope of this challenge. However, there are hopes for a breakthrough in establishing a more democratic UN Framework Convention on Tax following a recent proposal published by the UN Secretary General and a UN General Assembly resolution put forward by the African Group and adopted in November 2023.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank have recently developed agendas for gender, climate, and internal reform, yet consistently fail to recognize how their democratic deficits and imposition of strict austerity measures directly harm both people and planet. Even at the height of the pandemic, the IMF made the majority of their loans contingent on the uptake of austerity measures that would only exacerbate the worst impacts of the pandemic on the most marginalized. Transforming the role of the BWIs is a fundamental precondition to a more feminist global economic governance structure, and at the very least must begin with quota reform to shift power away from the richest countries currently dominating the IMF.

Despite the links between gender and trade being increasing mainstreamed by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the inclusion of gender policies in free trade agreements, global patterns in and governance of trade continue to take a siloed and neoliberal approach towards human rights. There is an escalating influx of trade deals negotiated outside the WTO which expand the remit of trade governance beyond explicit trade issues to include non-trade issues. These rules constrain the abilities of Global South countries to implement regulations in a way that is necessary to achieve gender equality. Meanwhile, extractivist fossil fuel capitalism continues to be promoted by the current trade regime, both through the use of investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms by corporations to arbitrate against countries implementing environmental standards, and through a new era of export-oriented “green” extractivism of critical raw materials like lithium.

The corporate capture of global governance and development is most evident in the growing trend towards “multistakeholderism” promoted even at the UN. Multistakeholderism in principle invites a range of stakeholders to participate in global governance (at the expense of a waning voice for governments), but in practice gives multinational corporations undue influence in policy-making, standard-setting, and the distribution of public goods. This has been evident in the UN’s increasing endorsement of private-public partnerships to close the “development financing gap,” and through proposed partnerships like the (now cancelled) agreement between UN Women and BlackRock, the world’s largest investment firm.

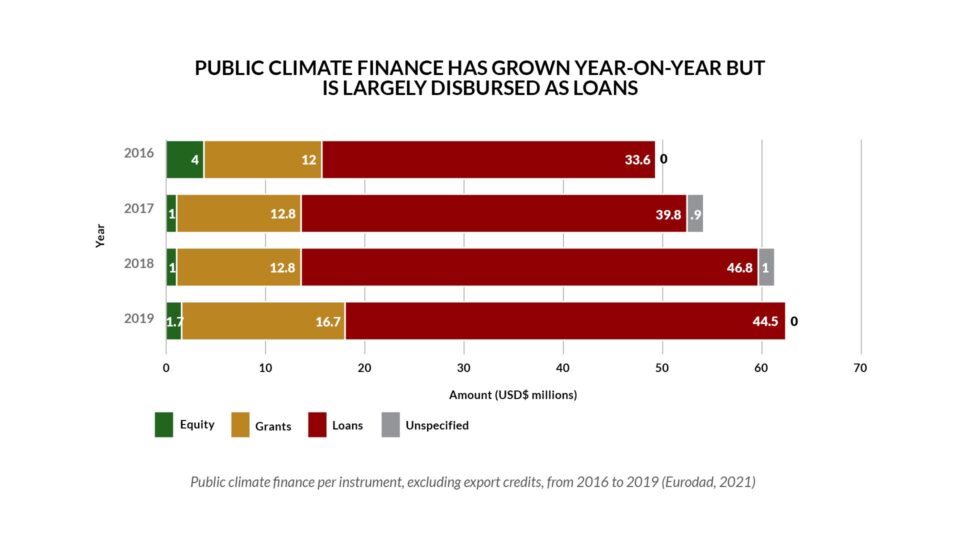

Although climate finance has grown year-on-year, Global North countries have failed to deliver on the commitment established in 2009 at COP15 to provide and mobilize US$100 billion in climate finance per year by 2020. Climate finance is also largely disbursed through loans, exacerbating the debt crisis, which locks countries further into climate vulnerability. It insufficiently focuses on addressing loss and damage, does not reach the countries that need it most, and fails to account for the need to be gender-responsive.

CRITICAL TRENDS IN NUMBERS

$237 BILLION

in windfall profits per year made by only 45 energy firms in 2021 and 2022 alone.

93%

of countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis are in or nearing debt distress.

90 OUT OF 107

IMF loans for COVID-19 economic recovery from 2020 to 2021 stipulated austerity measures as a condition for financing.

$1.4 TRILLION

spent by G20 countries on fossil fuel subsidies in 2022—outstripping ODA spend in 2022 by nearly sevenfold.

97

jurisdictions implemented decreases in their corporate tax rates between 2000 and 2022.

7 OF TOP 10

largest investment arbitration awards involved fossil fuel companies, ranging from pay-outs worth US$1.6 to US$40 billion.

$5.8 TRILLION

needed by global South countries to finance their climate agendas until 2030—far more than the US$100 billion pledge, itself only just fulfilled in 2022.

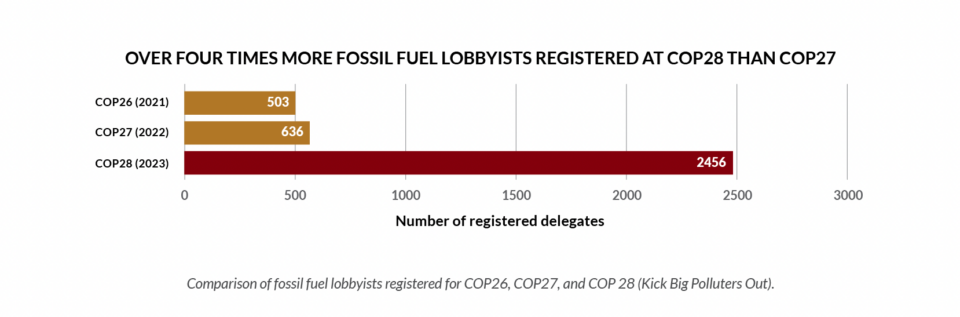

2456

fossil fuel lobbyists registered for COP28 in 2023—more than all the delegates from the ten most climate vulnerable nations combined.

500%

projected growth in demand for raw minerals by 2050 for the “green” transition (including lithium, cobalt, and nickel)—which will have to be extracted and exported primarily from the Global South.

CHAPTER 1: TRANSFORMING SYSTEMS FOR FEMINIST ECONOMIC AND CLIMATE JUSTICE

Global economic growth has been predicated on a model of increasing consumption and resource extraction, with catastrophic effects on the climate. While there was a brief decline in emissions in 2020 during the start of the pandemic, this trend sharply reversed in 2021. Out of 50 billion tons of carbon emissions released into the atmosphere in 2021, three quarters were produced by the burning of fossil fuels for energy purposes.[1] Global emissions are still far above what is required to meet the 1.5°C temperature threshold enshrined in the Paris Agreement, and people are facing a cost-of-living crisis through rising energy costs–but energy companies are raking in exorbitant profits. A total of 45 energy firms made an average of US$237 billion a year in windfall profits in 2021 and 2022, meaning they exceeded average profits in the previous four years by over 10%.[2]

At the same time, spurred by the global entrenchment of the neoliberal economic model in the 1980s, income inequalities have been on the rise nearly everywhere,[3] with sharp increases since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic both within and between countries.[4] Today, the world’s richest 10% capture over 50% of global income—while the bottom 50% of the global adult population share just 8.5%. Global inequality manifests directly into carbon emissions inequality, as excessive emissions of the world’s richest are a result of their consumption and investment patterns.

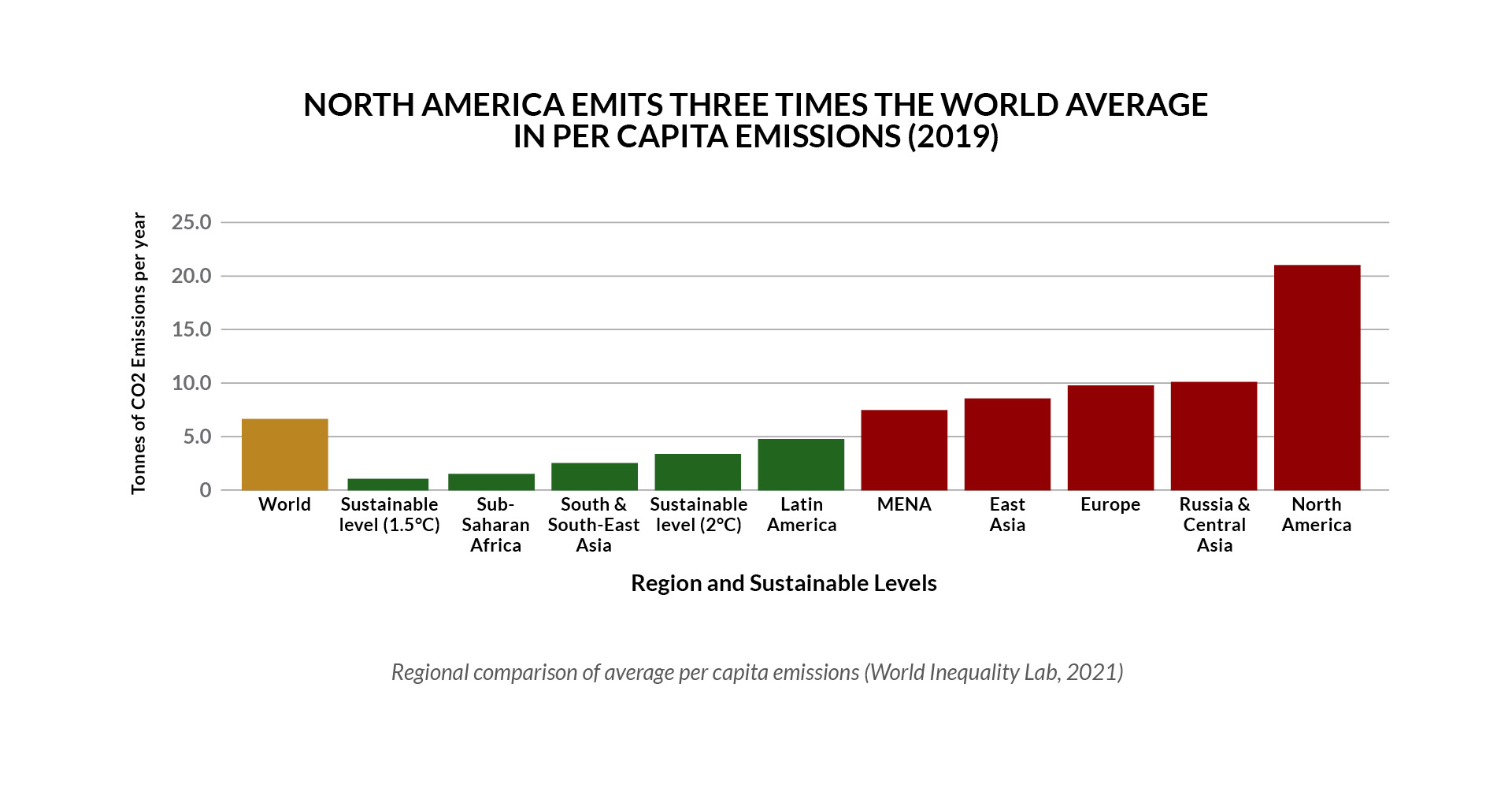

Over the past two decades, the world’s richest 10% have been responsible for over half of all carbon emissions, and just 1% of the global population accounts for half of all aviation emissions. In 2030, the world’s richest 1% are projected to have per capita consumption emissions 30 times higher than compatible with the Paris Agreement limit of 1.5°C temperature rise.[5] Data from 2019 shows that North Americans emit about three times the world average in emissions per capita—nearly 19 times the level required to keep warming under 1.5°C—while Sub-Saharan Africa emits just a quarter of the global average in per capita emissions.[6]

[1] World Inequality Lab, World Inequality Report 2022, 2021.

[2] ActionAid & Oxfam, Big business’ windfall profits rocket to “obscene” US$1 trillion a year amid cost-of-living crisis; Oxfam and ActionAid renew call for windfall taxes, 2023.

[3] Inequality is measured here using the T10/B50 ratio between the average incomes of the top 10% and the bottom 50%.

[4] Development Initiatives, Inequality: Global trends, 2023.

[5] Oxfam & the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP), Carbon inequality in 2030: Per capita consumption emissions and the 1.5⁰C goal, 2021.

[6] World Inequality Lab, World Inequality Report 2022, 2021.

this is the read more

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec a diam lectus. Sed sit amet ipsum mauris. Maecenas congue ligula ac quam viverra nec consectetur ante hendrerit. Donec et mollis dolor. Praesent et diam eget libero egestas mattis sit amet vitae augue.

Nam tincidunt congue enim, ut porta lorem lacinia consectetur. Donec ut libero sed arcu vehicula ultricies a non tortor. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aenean ut gravida lorem. Ut turpis felis, pulvinar a semper sed, adipiscing id dolor.

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT FINANCE

While still one of the most critical sources of transfers from Global North countries to the Global South, Official Development Assistance (ODA) remains far below promised or required levels. ODA makes up over 60% of external finance in least developed countries (LDCs).[1] Yet, since the UN target for developed countries to provide 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) for ODA was set 60 years ago, very few countries have met the target.[2] In 2022, members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC)—mandated to provide ODA—channeled only 0.36% of their GNI into ODA. In the same year, only five countries met or exceeded the UN target of 0.7% GNI for ODA.[3]

In 2022, ODA provided by DAC members amounted to US$204 billion, an increase of 13.6% from the previous year accounting for inflation.[4] However, much of this increase can be attributed to increased support to refugees within donor countries and in humanitarian aid, which contributed to approximately 14.4% and 10.9% of total ODA flows, respectively. This is largely due to a surge in ODA provided to Ukraine as a response to the Russian invasion.[5] If refugee costs and flows to Ukraine are discounted, ODA fell by 4% relative to 2021,[6] and declined overall by 0.7% to LDCs and 7.8% to sub-Saharan Africa.[7]

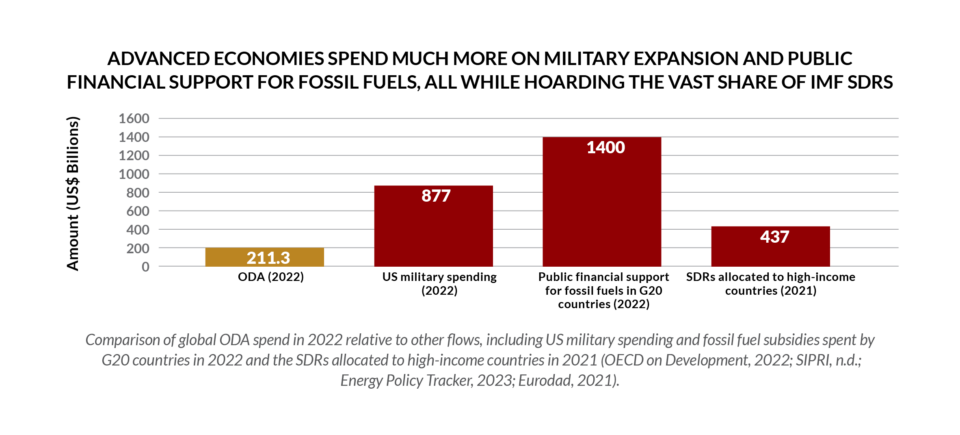

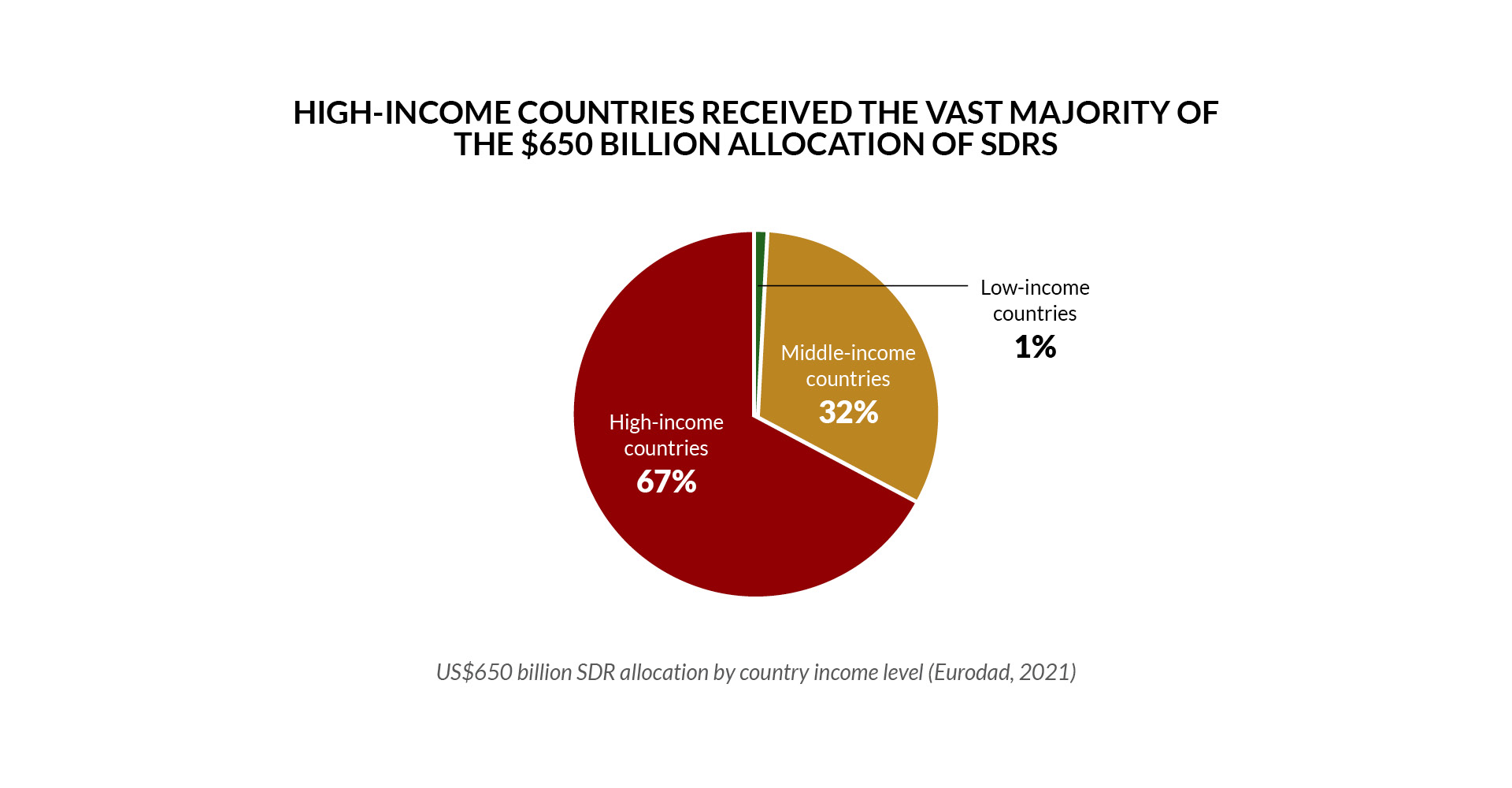

ODA spend is also insignificant relative to the amounts that rich countries spend on sectors that actively contribute to harm in the Global South. The US’s military expenditure in 2022 alone was four times that of cumulative ODA spend globally in the same year.[8] The G20—the world’s 20 largest economies—spent US$1.4 trillion on fossil fuel subsidies in 2022, outstripping ODA spend by nearly sevenfold.[9] At the same time, rich countries were allocated US$437 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) through the IMF’s most recent allocation in 2021, boosting their liquidity by far more than they provided in ODA.[10]

[1] OECD, External finance to least-developed countries (LDCs): A snapshot, 2022.

[2] OECD on Development, Official Development Assistance April 2023 Preliminary figures, 2023.

[3] This included Luxembourg (1%), Sweden (0.9%), Norway (0.86%), Germany (0.83%), and Denmark (0.7%).

[4] OECD on Development, Official Development Assistance April 2023 Preliminary figures, 2023.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Relief Web, On the Preliminary 2022 ODA Figures: What is the real deal on REAL aid?, 2023.

[7] OECD on Development, Official Development Assistance April 2023 Preliminary figures, 2023.

[8] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, n.d.

[9] Energy Policy Tracker, Fanning the Flames: G20 provides record financial support for fossil fuels, 2023.

[10] Eurodad, The 3 trillion dollar question: What difference will the IMF’s new SDRs allocation make to the world’s poorest?, 2021.

ALTERNATIVES FOR HUMAN WELL-BEING: DEGROWTH AND BUEN VIVIR

In recent years, alternatives to the model of endless economic growth have garnered increasing attention, with the concept of degrowth as one of the narratives gaining momentum.[1] Degrowth challenges the conventional pursuit of economic growth, advocating for a democratically led redistributive downscaling in production and consumption in industrialized countries to focus economic objectives around human wellbeing and ecological limits.[2] Degrowth policies include scaling down destructive sectors (such as fossil fuels, aviation, and livestock farming), and improving public services to deliver social outcomes without high levels of resource use—acknowledging that certain sectors (such as care) will require growth to meet basic needs. The degrowth approach holds that rapid decarbonization in wealthier countries will free up resources for low- and middle-income countries that still require growth for development.[3]

Alternative pathways for a socio-environmental future have also emerged from the Global South. The concept of buen vivir (or sumak kawsay in Indigenous Kichwa) originates from South America, with roots in the cosmologies of the Quechua peoples of the Andes. Buen vivir emphasizes living well through a harmonious relationship between human communities and the natural world. Both Ecuador and Bolivia have enshrined buen vivir and the Rights of Nature into their constitutions.[4] While fossil fuel industries have continued to extract resources in Ecuador over the past decade, there have been significant wins: in December 2021, the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court ruled in favor of the endangered Los Cedros Protected Forest against industrial copper and gold mining, setting a legal precedent for protecting the Rights of Nature.[5]

[1] Hickel, Less is More: How degrowth will save the world, 2020.

[2] Kothari, Demaria, & Acosta, Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy, 2015.

[3] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Declaration on the Right to Development, 1986; Hickel, Less is More: How degrowth will save the world, 2020. A forthcoming primer series on Degrowth for Social Justice, written by Emilia Reyes, will be published by the Action Nexus by February 2024.

[4] Kothari, Demaria, & Acosta, Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy, 2015.

[5] University of Sussex, New ‘Rights of Nature’ case will have major implications for protected forest and indigenous lands, 2022.

GLOBAL ADVOCACY SPOTLIGHT: REPARATIONS

Calls for reparations have reverberated across the formerly colonized countries of the Global South for decades, and have been growing in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and an escalating debt crisis. Reparations encompass both financial compensation and acknowledgment for the responsibility of past harms. Just as critically, reparations are also about democratizing the unjust global structures that have allowed the persistence of colonial legacies.[1]

Many of the calls for reparations are made in the context of demands for debt cancellation, as a “reparation and a right for the people who have been wounded and sacrificed on the altar of repaying odious and illegitimate debts, and who bear the brunt of the climate crisis.”[2] When British royals toured the Caribbean in 2022, calls for reparations were made in Jamaica by the Advocacy Network, and Jamaica’s National Reparations Commission began review of a petition seeking British compensation for the Transatlantic trade in enslaved persons. Meanwhile, in February 2023, amidst worsening debt crisis, Sri Lankan Prime Minister Dinesh Gunawardena called for compensation for atrocities committed by imperialists in Sri Lanka.[3]

[1] Gender and Development Network, Reparations as a pathway to decolonisation, 2023.

[2] WoMin African Alliance & CADTM Afrique, Call to the African Union, African Heads of State, International Financial Institutions, Chinese Lending Bodies and Private Creditors for a total and unconditional cancellation of African debt!, n.d.

[3] Gender and Development Network, Reparations as a pathway to decolonisation, 2023.

Overall, the world’s wealthiest countries and highest income-earners continue to bring in vast profits from fossil fuels, while neglecting to provide development finance according to their obligations. The transformation of our economic systems to promote economic, climate, and gender justice must be based on a fundamental challenge to the pursuit of economic growth and establish reparations for the countries that have been and will continue to be harmed by the climate crisis and the payment of illegitimate and colonial debt.

CHAPTER 2: DEBT

60%

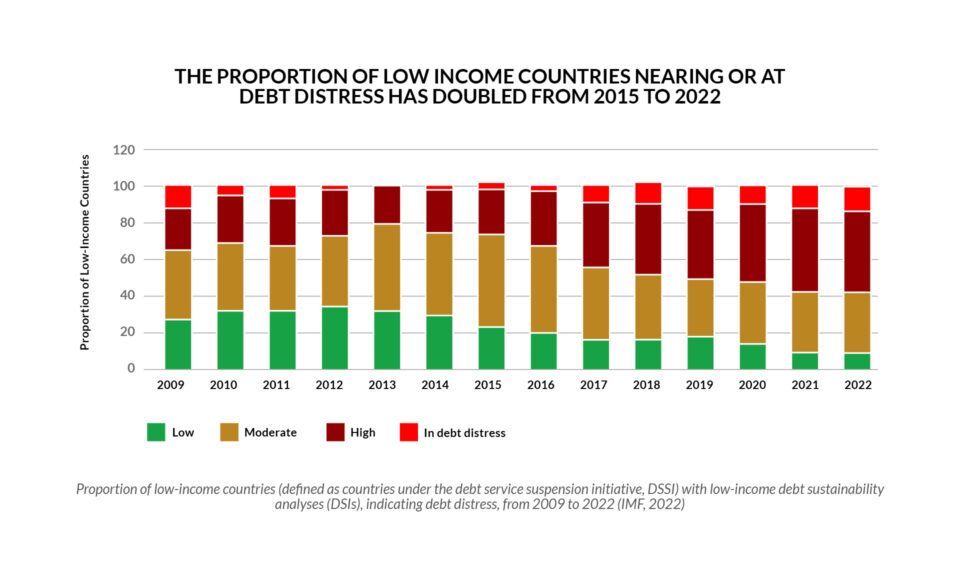

The proportion of low-income countries that are at high risk of or already in debt distress (doubling from 30% in 2015).

61 COUNTRIES

(most of which are highly climate-vulnerable) require immediate debt relief due to being at or near acute debt distress.

TWO THIRDS

of the countries with the highest debt payments between 2010 and 2018 also saw a decline in public spending.

In recent years, debt levels in the Global South have surged at an alarming rate, posing significant implications for women’s rights and economic wellbeing. Debt is simultaneously making climate-vulnerable countries unable to spend on mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage, and forcing governments to further contribute to climate change and biodiversity loss through environmentally destructive industries like fossil fuels, mining, and industrial agriculture to raise revenue to service their debts—magnifying the climate crisis at a time when 93% of countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis are at or nearing significant debt distress.[1]

The proportion of low-income countries that are at high risk of or already in debt distress has doubled from 2015 to 2022, rising from 30% to 60%.[2] The 2022 Global Sovereign Debt Monitor indicates that out of 148 surveyed countries in the Global South, 135 face critical levels of indebtedness. Among these, 39 countries are described as particularly critically indebted, which is more than three times the pre-pandemic number.[3]

[1] ActionAid, The Vicious Cycle: Connections between the debt crisis and climate crisis, 2023.

[2] IMF, Annual Report 2022: Crisis upon crisis, 2022.

[3] MISEREOR & Erlassjahr.de, Global Sovereign Debt Monitor 2022, 2022.

RISING DEBT IS CURBING SOCIAL AND CLIMATE SPENDING

Countries are spending more on external debt service than ever. Between 2010 and 2018, external debt payments by developing country governments increased by 83% as a proportion of government revenue. The amount of debt service payments owed to external creditors is currently at its highest level since the late 1990s.[1] In 2022, debt payments by LDCs and SIDS to G20 creditors amounted to US$21 billion, a 50% increase from US$14 billion in 2021. Despite the billions already paid in interest and capital repayments, in 2021 G20 countries continued to hold US$155 billion in bilateral debt from LDCs and SIDS.[2]

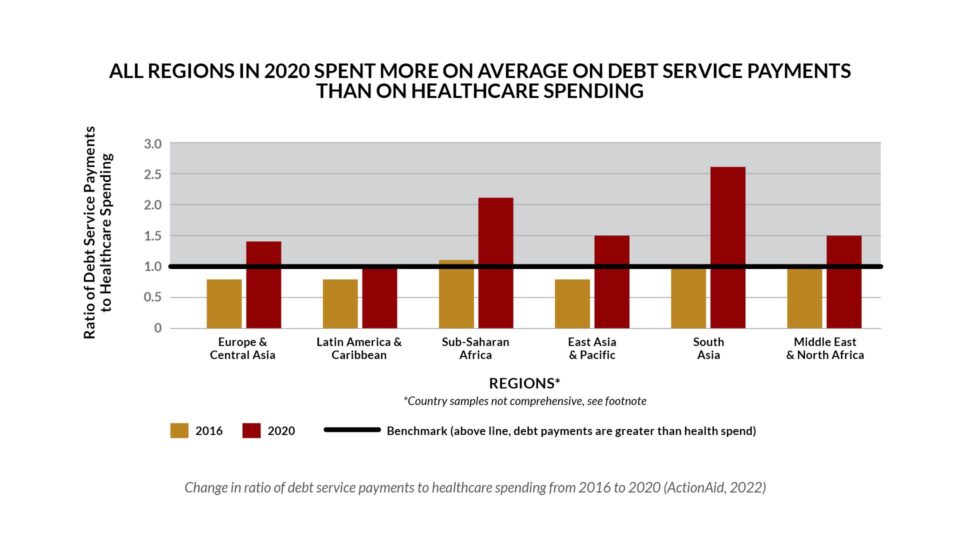

With mounting obligations to pay back creditors, countries have increasingly less fiscal space to invest in public services. In two-thirds of the countries with the highest debt payments between 2010 and 2018, public spending is declining.[3] In 2020, 36 countries spent more on external debt servicing than on education.[4] In the same year—at the height of the pandemic—countries on average spent more on debt service payments than on healthcare—which was not universally the case in 2016.[5]

Countries are also spending more on debt than they receive in climate finance and even total foreign aid in some countries. In 2021, 59 LDCs and small island developing states (SIDS) spent a cumulative US$33 billion on debt repayments while receiving only US$20 billion in climate finance. Both the total value of debt payments and the ratio of debt payments to climate finance were greater than in 2020. In nine countries, debt service payments in 2021 were greater than total foreign aid received.[6]

The data is based on a sample of 20 countries from Europe & Central Asia, 23 countries from Latin America & the Caribbean, 16 countries from East Asia & the Pacific, 8 countries in South Asia, and 10 countries in the Middle East & North Africa.

[1] Eurodad, Out of service: How public services and human rights are being threatened by the growing debt crisis, 2020.

[2] International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Climate-vulnerable indebted countries paying billions to rich polluters, 2023.

[3] Eurodad, Out of service: How public services and human rights are being threatened by the growing debt crisis, 2020.

[4] ActionAid, The Care Contradiction: The IMF, Gender, and Austerity, 2022.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The nine countries included Angola, Myanmar, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, the Maldives, Senegal, Belize, Lesotho, and Laos. IIED, Drowning in debt: help for climate vulnerable countries dwarfed by repayments, 2023.

INADEQUATE PROPOSALS FOR REFORM

In response to urgent calls for debt relief in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the G20 and Paris Club[1] established the Common Framework for Debt Treatments in November 2020. Contrary to calls for debt cancellation and hopes for a breakthrough in debt restructuring, the Framework is limited to debt restructuring and applies to only part of the debt held in only 73 low-income countries.[2] So far, only four countries have requested access to the Common Framework—Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia—and in no case has meaningful debt relief resulted.

Two years after requesting treatment in 2020, Chad is the only country to have finalized the process. Chad’s creditors decided that Chad did not require full cancellation of its debts, due to the country’s surging revenues from high oil prices—forcing climate-vulnerable Chad to maintain reliance on oil at a time when countries should be transitioning away from carbon-intensive fuels.[3]

(The conclusion of Zambia’s debt negotiations was announced at the 2023 IMF/World Bank Annual Meetings in Marrakech, also two years after its initial request under the Common Framework. But discrepancies between Zambia’s bondholders have effectively nullified the agreement, raising further, existential concerns about the Common Framework. This case will be explored in more detail in the forthcoming subsequent issue of the Trends Report, later in 2024.)

Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s application to the Common Framework resulted in a downgrading of its credit rating to a “CCC” from a “B”,[4] constituting a long-term negative effect on its availability to secure future credit and a warning to other countries that might consider applying. Further, by not including middle-income countries, the Common Framework also fails to address the debt crises currently experienced by countries like Sri Lanka and Suriname.[5]

In recent years, low- and middle-income economies have experienced a growing reliance on private creditors, especially bondholders. By 2021, private creditors accounted for 61% of the long-term public and publicly guaranteed external debt stock, amounting to US$3.6 trillion. While private creditors tend to attach fewer conditionalities that directly require austerity measures, they also tend to have less preferential rates than bilateral government creditors or multilateral institutions like the IMF, resulting in significant increases in debt service requirements.[6]

Yet the Common Framework does not oblige private creditors to participate,[7] which means that any debt relief countries receive may be redirected to service private debt, rather than on critical spending on climate or social services.[8] In fact, under the Common Framework, private creditors stand to profit from delaying debt relief—and may be intentionally holding out on negotiations to maximize profits on their bond holdings. If the bonds bought by private creditors from Ethiopia, Ghana, Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Zambia were bought at current depressed prices and paid in full, creditors could profit by US$30 billion on top of the premium interest rates they have already charged to cover their risk.[9]

Many countries have called for debt standstills in the face of climate emergencies or pandemics, with the World Bank and several bilateral creditors recently committing to include “pause clauses” in future debt contracts. Central to the Bridgetown Initiative conceived through the leadership of Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, these clauses will allow Global South countries to pause debt repayments in the face of future climate disasters. But these pause clauses do nothing to address the existing mountain of debt payments at a time when 61 countries—most of which are highly climate-vulnerable—require immediate debt relief due to being at or near acute debt distress. Measures agreed so far also fail to address other emergencies such as pandemics, or a longer-term need for climate adaptation.[10]

[1] The Paris Club constitutes a secretive and undemocratic cartel of creditors who have the primary purpose of maximizing returns on their loans. See Civil Society Statement on the Paris Club at 50: illegitimate and unsustainable, 2006.

[2] Eurodad, The debt games: Is there a way out of the maze?, 2023.

[3] Bretton Woods Project, Chad gets debt rescheduling, not relief, and is left dependent on oil revenues, 2022.

[4] Fitch Ratings, Fitch Downgrades Ethiopia to ‘CCC’, 2021.

[5] Eurodad, The debt games: Is there a way out of the maze?, 2023.

[6] World Bank Group, International Debt Report 2022, 2022.

[7] Eurodad, The debt games: Is there a way out of the maze?, 2023.

[8] World Bank Group, International Debt Report 2022, 2022.

[9] Debt Justice, The potential profit for bondholders if debts are not canceled, 2023.

[10] The Guardian, World Bank offers developing countries debt pauses if hit by climate crisis, 2023.

Credit: CADTM

LOCAL SITE OF STRUGGLE: “WE WANT OURSELVES ALIVE AND DEBT FREE!”

Women’s movements in Latin America are drawing links between debt, gender violence, and the financialization of social reproduction—and making these links visible in their political actions. A feminist reading of debt shows how the external debt contracted by nation states reinforces women’s dependencies on their household and increases their precariousness. Countries in debt distress often implement austerity measures, increased interest rates, and face currency depreciations that erode household purchasing power. The resulting increases in costs of living push households to take on debt—a particularly acute challenge for women-led households with extra unpaid care responsibilities. As families face challenges in affording their basic needs, they turn to banks and creditors that drive a cycle of further indebtedness.[1]

In this context, protests rallying around slogans challenging debt are not new in Argentina. The classic “IMF out” confronting IMF-imposed foreign debt and austerity traces back to the days of military dictatorship (1976-1983). In 2017, the Ni Una Menos Collective launched the slogan, “We want ourselves alive and debt free!” after the first international feminist strike, linking gendered and economic violence. Under this rallying cry, unions, workers, students, and gender-diverse peoples alike brought attention to the violence of debt in everyday life. In 2022, the International Women’s Day or #8M protesters united under the slogan, “The debt is owed to us,”[2] flipping the script around the debt owed to the women and gender-diverse people robbed by financial violence.[3]

[1] Limón, ¿Quién le debe a quién?, 2021.

[2] #8M refers to 8 March, the official date of International Women’s Day.

[3] Cavallero & Gago, A Feminist Reading of Debt, 2021.

GLOBAL ADVOCACY SPOTLIGHT: CALLS FOR A UN-BASED DEBT WORKOUT MECHANISM

Global South countries and civil society activists have long advocated for a UN-based debt workout mechanism as an alternative to the current international architecture governing debt, which is spearheaded by the undemocratic IMF. This UN mechanism would give equal voice to the interests of debtor countries, rather than the status quo of a creditor-dominated debt architecture.[1]

Yet, there has so far been little progress. In 2014, a window seemed to open in the UN as the G77 and China (the major negotiating bloc of developing countries) committed the General Assembly to working towards establishing a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt resolution. However, G7 governments— holders of a majority of low- and lower-middle income country debt—did not cooperate, and many boycotted the negotiations.[2] The process resulted in a set of principles, including the UN Basic Principles on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes and the UN Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD) Roadmap and Guide on Sovereign Debt Workouts.[3] While useful additions to the normative framework, these principles are non-binding and voluntary in nature, with little impact to customary international law.[4]

[1] Eurodad, 2023: A more just world is still possible, 2023.

[2] Eurodad, We can work it out: 10 civil society principles for sovereign debt resolution, 2019.

[3] UNCTAD, Roadmap and Guide for Sovereign Debt Workouts, 2015; UN General Assembly, Basic Principles on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes, 2015.

[4] Eurodad, We can work it out: 10 civil society principles for sovereign debt resolution, 2019.

Overall, multilateral ambition for debt reform has not provided meaningful debt relief or addressed the root causes of the escalating debt crisis. As climate change increases countries’ vulnerability to shocks, a growing debt burden and downgraded credit ratings constrain their ability to respond. Countries in the Global North are the least affected by the debt crisis and are home to the majority of private creditors who have incentives to delay debt relief. This inequitable dynamic means that debt resolution—and specifically, debt cancellation—must be driven by the more democratic space of the UN.

CHAPTER 3: TAXATION

99.3%

of all tax lost through corporate tax abuse profits wealthy countries.

OVER HALF

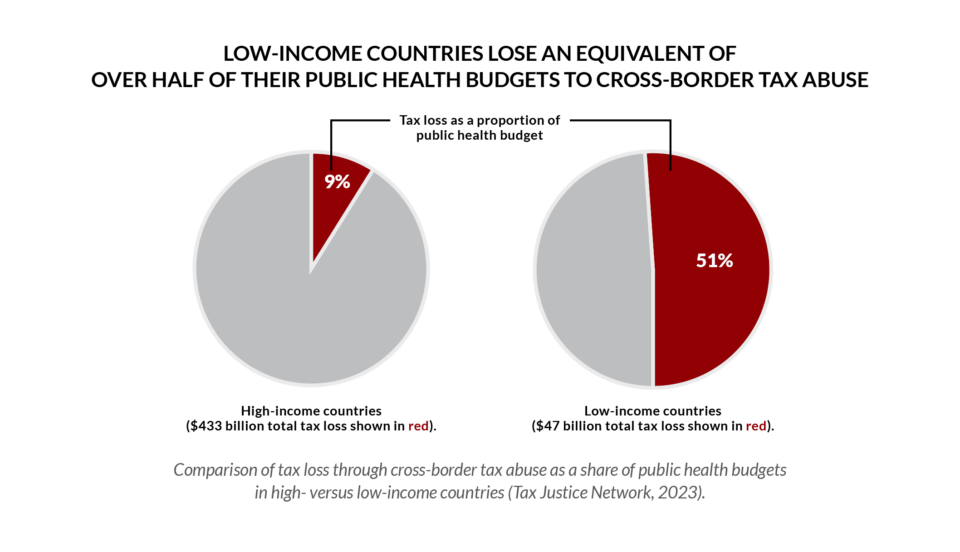

of low-income countries’ public health budgets are lost to cross-border tax abuse.

$480 BILLION

per year lost in global tax evasion and profit-shifting by MNCs and wealthy individuals.

A just and equitable tax system is critical to the redistribution of wealth both within and across countries, and to mobilize public finance for social wellbeing. Yet, for decades the international tax regime has been dominated by the world’s richest countries, particularly through the leadership of the OECD, an intergovernmental organization composed of 38 member countries (most of which are high-income) committed to the ideals of free market capitalism. The consequences of this asymmetric governance are egregious: countries in the Global South lose billions of dollars every year through tax evasion and avoidance, most of which is driven by multinational corporations based in OECD countries. Compounding these losses, countries’ taxation policies are often regressive—increasingly relying on consumption taxes that disproportionately burden low-income earners and women-led households

CORPORATE TAX ABUSE AND TAXATION SYSTEMS

OECD countries are home to the multinational corporations (MNCs) that drive the greatest tax-related illicit financial flows, and constitute some of the largest tax havens. Data from 2023 reveals that higher-income countries are responsible for 99.3% of all annual tax loss across the globe due to corporate tax abuse. Around 75% of those corporate tax losses end up in OECD-country tax havens in countries like the United Kingdom, British Overseas territory Bermuda, United States territory Puerto Rico, Singapore, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.[1] In 2023, Tax Justice Network reported that countries lose approximately US$480 billion a year to global tax evasion and profit-shifting by MNCs and wealthy individuals—of which US$311 billion alone, or nearly two-thirds, is lost through corporate profit-shifting to tax havens.[2]

These staggering levels of corporate tax abuse mean that low-income countries have even less space for public service provision or investments in climate finance. Although larger economies sustain the largest losses (US$433 billion per year based on 2022 data), lower-income countries’ losses (US$47 billion per year) are far more impactful when considering the proportion of their budget spent on essential public services such as welfare, health, or education. A US$433 billion loss for high-income countries makes up about 9% of their public health budget, whereas a US$47 billion loss in tax revenue for low-income countries is equivalent to 49% of their public health budgets.[3]

On top of the billions lost through tax-related illicit financial flows, corporate income tax rates have generally declined over the past few decades, further curbing the fiscal space of countries to invest in public services. Since the 1980s, as neoliberal policies have accelerated, global average statutory corporate tax rates have fallen by more than half, from 49% in 1985 to 24% in 2018.[4] Most countries today have a corporate tax rate below 30%.[5] Most recently, in 2022, ten countries decreased their corporate tax rates, reflecting a continuation of the general trend in countries cutting their corporate income tax. In the same period, only six countries increased their top corporate tax rates.[6] This change reflects existing pressures to encourage foreign direct investment.[7]

At the same time, countries are encouraged by the IMF to increase regressive taxes on consumption goods, disproportionately burdening low-earners. During COVID-19, out of 107 loans negotiated between governments and the IMF between March 2020 to March 2021 for economic recovery, the austerity will drive inequality worldwide</a>, 2021.</p>" class="definition_link">IMF proposed an increase in value-added tax (VAT) in 14 countries.[8] This is a continuation of a well-established trend: between 1990 and 2017, countries overwhelmingly tended to replace progressive income and corporate taxes with regressive taxes like VAT as part of IMF loan conditionalities. Instead of locating the burden of taxation on top-earners who can afford to pay more in taxes, VAT increases further harm to women by reducing their ability to meet their basic needs. This is because VAT—as a regressive consumption tax collected by sellers across the supply chain—lowers purchasing power of all consumers, rather than being a form of targeted and direct taxation on wealthy income-earners.[9]

[1] Tax Justice Network, State of Tax Justice 2023, 2023.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] World Inequality Lab, World Inequality Report 2022, 2021.

[5] Tax Foundation, Corporate Tax Rates Around the World, 2022, 2022.

[6] The ten countries that reduced their corporate tax rates are the Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Tajikistan, France, Greece, Monaco, and French Polynesia. Meanwhile, the six countries that increased their rates are Colombia, South Sudan, Netherlands, Turkey, Chile, and Montenegro, although Turkey is set to re-establish their pre-2022 corporate tax rate in 2023.

[7] Tax Foundation, Corporate Tax Rates Around the World, 2022, 2022.

[8] Oxfam, Adding Fuel to the Fire: How IMF demands for austerity will drive inequality worldwide, 2021.

[9] Ibid.

INADEQUATE SOLUTIONS FOR REFORM

The OECD (which, as mentioned above, functions outside the global multilateral system and consists of only rich country governments) has led the charge to reform the global tax system to address tax-related illicit financial flows, particularly since 2016 with the introduction of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS).[1] Though the Inclusive Framework represented the first plausible opportunity for non-OECD countries to partake in global rule-setting on tax, it excludes over two-thirds of LDCs. Only 27 out of 54 African countries are members of the Framework—in part because many countries are refusing to partake in a proposal over which they had little say.[2] While it was meant to come into effect in 2023, the implementation of the Inclusive Framework has been delayed to 2024.[3]

The Inclusive Framework aims to force the world’s largest MNCs to pay a greater share of taxes in countries where they are making profits. While this is a welcome departure from the previous system, where taxation largely depended on MNCs having a physical presence, its minimal scope is a significant concern. The Framework applies only to super profits above a 10% return on revenue, and only for slightly over 100 large MNCs with a global turnover of at least €20 billion. It also does not cover taxation of MNCs for digital services, which would let companies like Amazon off the hook.[4]

As endorsed by G20 leaders in 2021, the Framework also seeks to establish a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%.[5] However, enforcement is a matter of national discretion, and applies only to MNCs with a global turnover exceeding €750 million.[6] This leaves out around 80 to 90% of corporations around the world.[7] Further, most progressive analysis agrees that the 15% minimum is too low, with UN and independent panels calling for global corporate tax rates between 20 and 30%.[8] A minimum corporate tax rate of 25% would drive almost US$17 billion more in tax revenue for the world’s 38 poorest countries.[9]

Besides OECD-led reforms, a key development in the push for combating global tax abuse is the UNCTAD release of measurement tools and methodological guidelines on illicit financial flows. In 2020, UNCTAD and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) published a Conceptual Framework for the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows, which constitutes the first attempt to conceptualize illicit financial flows and measure them from selected legal markets as an attempt to generate better statistics to reflect a clearer reality of these flows.[10]

[1] BEPS refers to strategies used by corporate entities to exploit mismatches in tax rules to shift their profits to low or no-tax jurisdictions.

[2] IMF, International Corporate Tax Reform, 2023.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eurodad & LSE, Is the OECD 2021 corporate tax deal fair?, n.d.

[5] The Guardian, G20 Leaders to Endorse Biden Proposal For Global Minimum Corporate Tax Rate, 2021.

[6] IMF, International Corporate Tax Reform, 2023.

[7] Eurodad & LSE, Is the OECD 2021 corporate tax deal fair?, n.d.

[8] In 2021, the UN Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (FACTI) Panel recommended a 20 to 30% global corporate tax. Meanwhile, the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT) called for a minimum 25% global corporate tax rate.

[9] Oxfam, OECD deal on track to become rich country stitch-up: Oxfam, 2021.

[10] UNCTAD, Conceptual Framework for the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows, 2020.

Credit: Tony Karumba / AFP

LOCAL SITE OF STRUGGLE: MASS PROTESTS IN KENYA OVER REGRESSIVE TAX HIKES ON ESSENTIAL GOODS

In early 2023, the Kenyan Government introduced a new financial bill to increase public revenues to service their heir international debt payments, which includes a 1.5% housing levy and doubles the tax on petroleum products from 8% to 16%.[1] These changes instantly triggered an increase in transportation costs, which ricocheted across other sectors, hiking the prices of basic commodities such as bread and maize flour. This has had a significant impact on the net income of low earners, and adds to the burden on women and women-led households because they spend a greater proportion of income on the essential goods included in the tax hike.[2] The increase in transportation costs may also limit women’s mobility, particularly those living in rural areas.[3]

As MNCs and wealthy individuals continue to make billions through tax abuse and evasion, Kenyan protesters took to the streets in July 2023 over the tax hikes on essential goods. The protests have been urgent and severe: more than 23 people have died and hundreds were arrested.[4]

[1] Al Jazeera, Kenya braces for 3 days of anti-government protests: All the details, 2023.

[2] Al Jazeera, Kenya’s opposition set for a second day of tax hike protests, 2023.

[3] DW, Kenya’s planned tax hikes spark anger, 2023.

[4] Al Jazeera, Kenya’s opposition set for a second day of tax hike protests, 2023.

GLOBAL ADVOCACY SPOTLIGHT: UN FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON TAX

Civil society organizations have long advocated for a UN Convention on Tax as “a major step forward in the international fight against tax havens and international tax dodging by the world’s wealthiest individuals and corporations.”[1] This would be a binding multilateral convention similar to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), empowering governments to exercise greater sovereignty over tax decisions affecting their economies and diverting power away from the OECD-led tax governance system.[2] These changes would have great potential to improve wealth taxation, tax excess profits of fossil fuel corporations, end tax avoidance by multinational corporations, combat financial secrecy, and shift the power of international tax negotiations to be more inclusive and effective.[3]

In a landmark step towards overhauling the global tax governance system, in November 2023 the UN General Assembly agreed a resolution to form a UN Framework Convention on Tax. Submitted by the African Group of States, and building on momentum highlighted by the UN Secretary-General’s proposal in August 2023,[4] the resolution sets in motion an intergovernmental committee to determine the terms of reference for the convention, by August 2024.[5] Though Global North countries have expressed objections to the proposal, a united front across civil society and the Global South could ensure that a new global tax governance system is finally within reach.[6]

[1] Eurodad, Growing support for a UN Convention on Tax, 2023; see also Eurodad, Proposal for a United Nations Convention on Tax, 2022 for a full proposal on what this convention could look like.

[2] Tax Justice Network, State of Tax Justice 2023, 2023.

[3] Global Alliance for Tax Justice, Tax Justice, Not Greenwashed “Innovation”: A Feminist Perspective on the Paris Summit, 2023.

[4] UN General Assembly, Promotion of inclusive and effective international tax cooperation at the United Nations: Report of the Secretary-General (Advance unedited version), 2023.

[5] Global Policy Forum, Reforms to the global financial architecture, 2023.

[6] Eurodad, A UN Convention on Tax – momentum just keeps growing, 2023. See also Global Alliance for Tax Justice, “Historic UN Tax Vote – A Tremendous Win for Africa and the Global Fight for Tax Justice,” 2023.

Overall, countries continue to be victims of rampant tax abuse, all while they are pressured to keep corporate and income tax low nationally while increasing regressive consumption taxes to make up for the shortfall in public revenues. The OECD-dominated global tax system will do little to resolve these structural inequities, but hopes for a breakthrough in establishing a UN Framework Convention on Tax have finally been coming to light.

CHAPTER 4: GLOBAL ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE

90 OUT OF 107

IMF loans for COVID-19 economic recovery from 2020 to 2021 stipulated austerity measures as a condition for financing.

$15 BILLION

invested by the World Bank to support fossil fuel projects and policies since the Paris Agreement.

36

advanced and high-income economies have the strongest voting share in the IMF and hold approximately 59% of IMF votes.

Since their inception at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference—a process led by the colonial Global North and attended by only 44 countries—the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs, comprised of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund) have held significant sway in global economic governance. Their colonial roots manifest in a democratic deficit in decision-making, leading to limited resource access for Global South countries and the imposition of strict austerity measures to impose control on public spending through loan conditionalities. These measures disproportionately impact low-income countries with little influence on decision-making—and within these countries, women and gender-diverse people in particular.

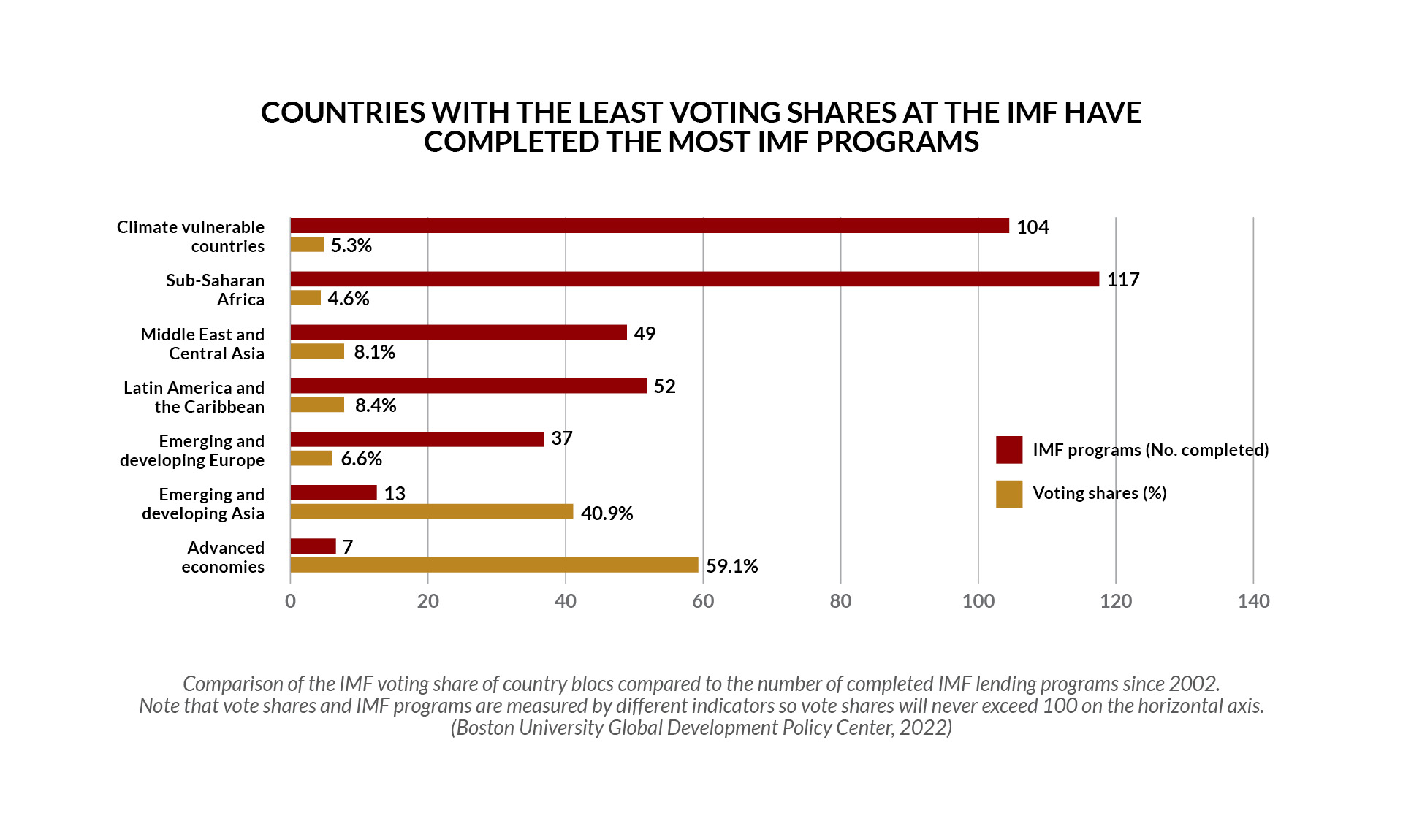

DEMOCRATIC DEFICITS IN THE BWIS

The IMF has long been criticized by civil society activists and Global South countries for its one-dollar-one-vote, quota-based decision-making structure. Around 36 advanced and high-income economies have the strongest voting share in the IMF and hold approximately 59% of IMF votes.[1] GDP comprises half of the determinant for a country’s vote share in the IMF—meaning richer countries have greater decision-making power—but 30% of quota allocations are determined by a country’s “openness”: its volume of current account payments and transfers. This is based on the IMF’s subjective interpretation that integration through international trade and finance is beneficial for countries, despite evidence that liberalization leaves many countries in the Global South vulnerable to global market fluctuations and financial crises.

Quota allocations also determine the amount of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) distributed to IMF member states, meaning wealthy countries receive a majority of the allocation. Of the US$650 billion in new SDRs proposed in 2021, only US$7 billion has gone to low-income countries, with the vast majority being added to the coffers of rich Global North countries unable to transfer them to other countries due to the stipulations of national legislation.[2]

Any proposed reforms of the IMF and their role in global economic governance will be impossible without meaningful quota reform. The U.S. has an automatic veto power on quota increases and the distribution of voting shares because such decisions require an 85% majority, and the U.S. itself has an over 15% voting share. The IMF periodically reviews its quotas, with the most recent review concluding in December 2023 without changing the formula or making even small adjustments. Only two increases in quota shares have been implemented in the past 30 years, demonstrating the rigidity of the existing system.[3]

The World Bank is also governed by undemocratic decision-making processes, as evidenced by the assignment of former Mastercard CEO Ajay Banga as the new World Bank president at the beginning of 2023. Banga’s nomination resulted from the BWIs’ colonial leadership selection process, determined by a “gentleman’s agreement” where the World Bank president is always a U.S. national and the IMF managing director is always a European.[4] Banga, whose orientation towards private capital and lack of development experience should have disqualified him, was supported by other Global North countries even before the nomination period technically began.[5]

[1] Bretton Woods Project, IMF and World Bank decision-making and governance, 2020.

[2] Eurodad, The 3 trillion dollar question: What difference will the IMF’s new SDRs allocation make to the world’s poorest?, 2021.

[3] Devex, Opinion: IMF rules continue to be rigged against the world’s poorest, 2023. and Boston University Global Development Policy Center, No Voice for the Vulnerable: Climate change and the need for quota reform at the IMF, 2022.

[4] Center for Global Development, Time, Gentlemen, Please, 2019.

[5] Bretton Woods Project, Democratic Deficit in the World Bank Presidential Appointment, 2023.

IMF AUSTERITY UNDERMINES HUMAN RIGHTS

Since the introduction of structural adjustment programs in the 1980s, the IMF has frequently attached policy conditionalities in their lending to developing countries, stipulating reductions in public expenditure that have increased poverty and income inequality. Due to their dominant role in IMF decision-making, advanced economies determine the conditions attached to IMF lending—without ever having to take on IMF policy advice or endure the effects of these conditions themselves.[1]

Despite its alleged mandate to assist countries in recovering from the pandemic, the IMF continues to push austerity alongside its COVID-19 programming. Out of 107 loans worth US$107 billion negotiated between governments and the IMF for post-COVID-19 economic recovery from March 2020 to March 2021, 90 loans required austerity measures as a condition for financing. In these loans, the IMF proposed public expenditure cuts for 55 countries, wage bill cuts and freezes for 31 countries, and an increase in value-added tax in 14 countries.[2] This has eroded the welfare state and the role of public finance, curbing access to social services for women and others facing discrimination.[3]

Further, the IMF’s response to COVID-19 has only continued to exacerbate sovereign debt at the cost of social service provision.[4] By 2023, the governments of 59 low- and middle-income countries will be spending less on social services than they did in the 2010s.[5] Where there are provisions for social spending, IMF loans tend to favor targeted programs rather than universal social protection.[6] Targeted programs have a narrow scope for protection and use selection processes that are costly, inaccurate, and ultimately exclude many people from applying, as well as increasing the stigma around social protection due to the need to apply.[7]

In response to criticisms of IMF-imposed austerity, since 2019, the IMF has been implementing “social spending floors” as part of their loan conditionalities. These floors represent a minimum level of public spending on social services such as education, health, and social protection. Countries must agree to maintain floors, even under the fiscal consolidation measures often required by IMF-supported programs. However, social spending floors typically take a backseat to austerity conditionalities in implementation. An Oxfam analysis of IMF social spending floors in loan programs to low- and middle-income countries in 2020 to 2021 found that for every US$1 the IMF encouraged countries to spend on public goods, it has demanded that they cut four times more through austerity measures.[8]

[1] Boston University Global Development Policy Center, No Voice for the Vulnerable: Climate change and the need for quota reform at the IMF, 2022.

[2] Oxfam, Adding Fuel to the Fire: how IMF demands for austerity will drive inequality worldwide, 2021.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eurodad, Out of service: How public services and human rights are being threatened by the growing debt crisis, 2020.

[5] Oxfam, IMF Social Spending Floors: A fig leaf for austerity?, 2023.

[6] Recommendations for targeted social spending were observed in Sierra Leone, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Peru, Chad, Georgia, Mauritania, Mongolia, Madagascar, Egypt, and Colombia.

[7] Oxfam, Adding Fuel to the Fire: how IMF demands for austerity will drive inequality worldwide, 2021.

[8] Oxfam, IMF Social Spending Floors: A fig leaf for austerity?, 2023.

NEW FORAYS INTO GENDER AND CLIMATE

The World Bank’s new 2023-2030 Gender Strategy attempts to provide a new focus on care and social protection in the Bank’s approach to poverty reduction and inclusive growth.[1] It has drawn much criticism,[2] primarily because the Strategy fails to consider the gendered impact of the World Bank’s own role in development policy financing, including its recommendations for fiscal consolidation and regressive tax-focused loans. It also tends to reduce women to “untapped sources of income.”[3]

Similarly, the IMF Gender Strategy released in 2022 fails to address the harmful impacts of IMF macroeconomic policy and the root causes of gender inequality, opting instead for a business-friendly approach to women’s “empowerment.” In an open letter to the IMF sent in 2022, a group of 178 feminist organizations and 124 individuals rejected the IMF Gender Strategy and called out the IMF’s harmful history of fiscal consolidation and structural adjustment, elaborating on how this history has been antithetical to achieving gender equality.[4]

The Evolution Roadmap is the World Bank’s most recent iteration of their long-term vision and strategy—although instead of addressing much-needed governance reforms, it appears to only reaffirm business-as-usual. The Roadmap has drawn much criticism for its emphasis on return-seeking capital and reliance on South-to-North extractive processes, while omitting any recognition of the democratic deficit in global economic governance. It also reaffirms the Bank’s Cascade approach, which is premised on incentivizing and mobilizing private sector and commercial finance into development.[5]

As part of its new sensitivity to climate change, the IMF established the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) in 2022, a new source of loans funded by unused SDRs targeted towards SIDS and climate vulnerable countries. As of April 2023, the RST held about US$40 billion in SDRs—still a mere fraction of the SDRs held by high-income countries.[6] As a loan-based trust, the RST will add to the debt burdens of countries borrowing from it. In addition, countries’ access to RST loans is contingent upon having another “traditional” IMF loan program, with the typical set of attached conditionalities and austerity impacts. Without adequate debt cancellation, there is a high likelihood that loans from the RST will only be used to service existing debts.[7]

More broadly, the BWIs’ increasing push to position themselves as key actors in climate finance further undermines the need for a democratic just transition. The World Bank has invested US$15 billion to support fossil fuel projects and policies since the Paris Agreement.[8] In 2022 alone, it is estimated that US$3.7 billion in trade finance from the World Bank went to oil and gas.[9] A shift in decision-making power for climate finance from the more democratic space of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to the undemocratic IMF and World Bank would be a regressive move, increasing the prospects of loan-based finance and lack of alignment with the Paris Agreement.[10]

[1] World Bank, World Bank Gender Strategy 2024-2030, 2023.

[2] Bretton Woods Project, World Bank’s new gender strategy: Concerns about approach to social protection and gender-blind macroeconomic reforms remain, 2022; Bretton Woods Project, Spring Meetings 2023 Wrap Up: Bretton Woods Institutions fail to deliver a transformative ‘evolution, 2023.

[3] Bretton Woods Project, Spring Meetings 2023 Wrap Up: Bretton Woods Institutions fail to deliver a transformative ‘evolution’, 2023

[4] Civil society joint statement, Feminists Reject International Monetary Fund’s Strategy Toward Mainstreaming Gender #NotInOurName, 2022.

[5] Civil society joint statement, Civil Society calls for rethink of World Bank’s Evolution Roadmap as part of wider reforms to highly unequal global financial architecture, 2023.

[6] Reuters, IMF’s Georgieva says 44 countries interested in new resilience trust loans, 2023.

[7] Debt Justice and CAN International, The debt and climate crises: Why climate justice must include debt justice, 2022.

[8] ActionAid, The Vicious Cycle: Connections between the debt crisis and climate crisis, 2023.

[9] Urgewald, Is the World Bank giving billions of trade finance to fossil fuels?, 2023.

[10] ActionAid, The Vicious Cycle: Connections between the debt crisis and climate crisis, 2023.

Credit: APMDD

LOCAL SITE OF STRUGGLE: CLIMATE JUSTICE IN PAKISTAN — DEBT CANCELLATION IS A RIGHT, NOT A FAVOR

Climate-vulnerable countries like Pakistan have called for debt relief amidst the ever-worsening impacts of the climate crisis, but have only been saddled with even more debt by institutions like the IMF. In 2022, Pakistan was devastated by floods that affected 33 million people and amounted to losses estimated at US$40 billion. Pakistan ranks in the bottom three countries on the Global Gender Gap Index, with severe consequences when climate disasters strike: not only do women suffer more casualties from climate disasters, but their forced migration post-disaster constitutes a significant disrupter for girls and women, further limiting their mobility, access to education, and economic autonomy.[1]

Before the floods, Pakistan decreased climate spending by at least 25% between FY2021-2022 as a result of actions to secure IMF loans—and at the height of the floods, IMF programs dampened consumer purchasing power and reduced public spending at a time when people needed it most.[2] Exacerbating the worst effects of the climate crisis and undermining recovery for the most marginalized, the IMF bailouts were worth only a fraction of the total damages to Pakistan, with a significant portion of the money directed towards debt repayment.[3] Amidst this crisis, Pakistani activists and intellectuals have called for climate justice through debt reparations, particularly given that Pakistan’s underdevelopment is rooted in a history of exploitation as a British colony, the subsequent stranglehold of structural adjustment, and the debt taken on by unaccountable rulers.[4]

[1] Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms (ALIGN), What do we mean by ‘there’s no climate justice without gender justice’?, 2022.

[2] Alliance for Climate Justice and Clean Energy, Alternative Law Collective, & Recourse, How are the IMF and the World Bank shaping climate policy? Lessons from Pakistan, 2023.

[3] Peoples Dispatch, ‘The ax always falls on the most vulnerable’: Pakistan demands debt cancellation and climate justice, 2022.

[4] Equal Times, After calamitous floods, Pakistan makes a compelling case for climate reparations, 2022.

GLOBAL ADVOCACY SPOTLIGHT: TOWARDS A FOURTH UN CONFERENCE ON FINANCING FOR DEVELOPMENT

The UN Financing for Development (FfD) process remains the most legitimate and democratic forum for global economic governance. It follows the UN General Assembly dictum of one country, one vote, with civil society participating as observers. Twenty years after the FfD process began, the world faces climate and cost-of-living crises, new waves of austerity, and increasing inequalities—further highlighting the critical role the process should take in global economic governance. The recent decision to consider convening a fourth FfD Summit in 2025 at heads of state level offers a powerful opportunity to recenter global economic governance at the UN, rather than in undemocratic spaces such as the BWIs.

Ideally, the Fourth FfD Conference should mobilize governments to finally operationalize longstanding calls for new UN bodies on issues like tax and debt. Civil society must be active in pushing for a fourth FfD and outcomes that would guarantee more decision-making power for global South governments and enable pathways towards economic and climate justice.

Overall, while there is much discussion on the outsized role played by the BWIs in global economic governance, there is little traction towards transforming this structure. There will be no meaningful reform of the role of BWIs in global economic governance if the IMF does not dramatically increase quota shares for the Global South. Without fundamental changes in global economic governance, the BWIs will only continue down the track of harmful conditionalities and predatory loans, whilst promoting a façade of intent to reform through their gender strategies and practices like the IMF’s social spending floors. The IMF and World Bank cannot serve as agents towards gender, climate, or economic justice so long as they fail to interrogate where their own interventions are causing harm. Instead of attempting to expand their mandates into the gender and climate arenas, the BWIs must first recognize how their policy advice and loan conditionalities undermine the role of the state and the multilateral system in protecting both public services and public goods.[1]

[1] ActionAid, The Care Contradiction: The IMF, Gender, and Austerity, 2022.

CHAPTER 5: TRADE

7 OF THE TOP 10

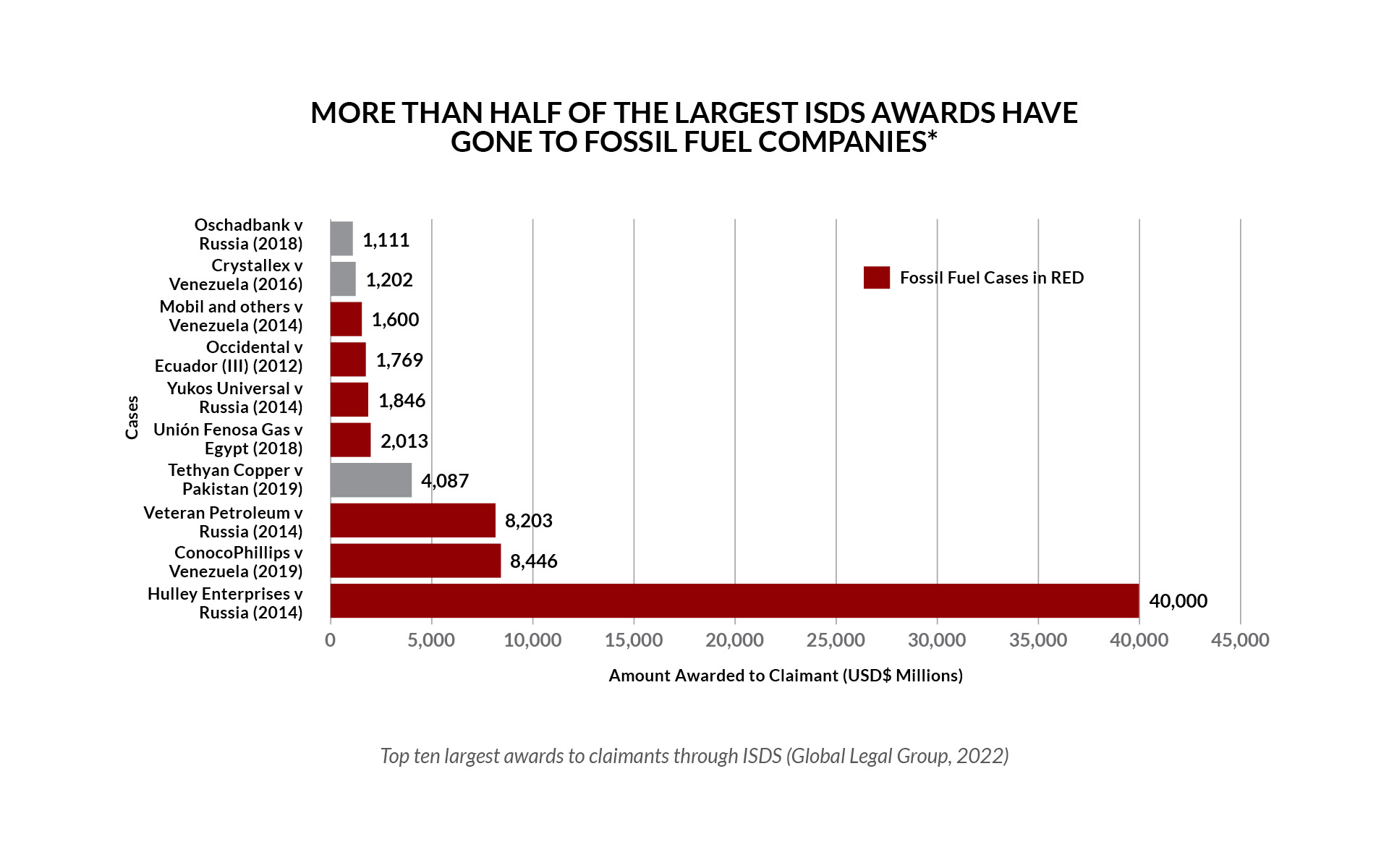

largest investment arbitration awards involved fossil fuel companies, ranging from pay-outs worth US$1.6 to US$40 billion.

500%

projected growth in demand for raw minerals by 2050 for the “green” transition (including lithium, cobalt, and nickel)—which will have to be extracted and exported primarily from the Global South.

20%

of known investor-state dispute settlements are linked to fossil fuel sector investments, with more than two thirds of these cases being won by investors.

Global patterns in trade and investment have historically benefited from the exploitation of women’s paid and unpaid labor while remaining blind towards the gender differentiated impacts of trade policies. Trade governance continues to take a siloed and neoliberal approach towards women’s human rights, within a system that has historically prioritized the interests, profits, and rights of large corporations and wealthy countries.

WITHIN AND BEYOND THE WTO: TRANSFORMING GLOBAL TRADE RULES

In recent years, links between gender and trade have been increasingly mainstreamed through both rhetoric and the inclusion of gender policies and chapters in multilateral, regional, and free trade agreements. In 2017, the World Trade Organization (WTO) initiated a Joint Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment, which failed to recognize the WTO’s own role in deepening inequalities, such as through its continued policies around liberalization, privatization and deregulations.[1] Instead, it was used to introduce new issues on the WTO’s agenda, centering on how women can be integrated into global value chains for economic “empowerment.”[2]

The governance of trade more broadly mirrors the WTO’s failure to recognize how trade liberalization has often facilitated harm in the Global South. The multilateral trade rules of the WTO are being increasingly crowded by the influx of trade deals signed and negotiated outside of the WTO. These include the recently concluded EU-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement and African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the now in force Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the newly launched Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF).[3] Most of these agreements go beyond the WTO’s trade rules and will likely add to more harm to the existing ones by significantly curbing the space for developing countries to enact policy changes in the areas governed by these agreements.

The AfCFTA illustrates the harms of new generation trade deals. The AfCFTA came into force in January 2021, stipulating that its members (which include most countries in the African continent) agree to eliminate tariffs on most goods and services within 5 to 13 years to promote African economic integration. This rapid and aggressive liberalization will drive significant losses in public revenue that could prompt further curtailment of the provision of public services and may drive regressive tax hikes on essential consumption goods.[4]

One of the most significant characteristics of these new trade agreements is that they go beyond “old” trade issues like tariffs, goods, services, investment, and Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), including new issues and areas that are only remotely related to trade. The new issues range from the digital economy, government procurement, subsidies toward small fisherfolk, and food security related initiatives.[5] The rules governing these new issues in turn constrain developing countries’ abilities to enact policies for development, the regulation of MNCs, and the management of crises. This is particularly the case when trade commitments pressure developing countries to eliminate subsidies and tariffs which are instrumental to their development—even though developed countries have historically and presently been allowed to protect their economies through their control over technology and standard and non-tariff barriers.[6]

Challenges to the current IPR regime gained momentum in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as a key demand of Global South countries and activists, including feminist collectives. [7] In June 2022, the WTO finally approved a waiver of intellectual property protections for COVID-19 vaccine patents, previously established under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).[8] The original TRIPS waiver proposal was submitted to the WTO by India and South Africa in 2020, and blocked by the United States and European Union. The eventual TRIPS waiver was a watered-down version of the original proposal—a classic case of “too little, too late.” Yet, prior to the pandemic, many Global South countries and feminist civil society advocates believed challenges to the IP regime would not be taken seriously, making the TRIPS waiver a necessary—but not sufficient—step towards questioning the current regime.[9]

[1] Asia Pacific Forum on Women Law, and Development, Statement: Women’s Rights Groups Call on Governments to Reject WTO Declaration on Women’s Economic Empowerment, 2017.

[2] ActionAid, From Rhetoric to Rights: Towards Gender-Just Trade, 2018.

[3] FEMNET, The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and Women: A Pan African Feminist Analysis, 2021; House of Commons Library, The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), 2023.

[4] FEMNET, The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and Women: A Pan African Feminist Analysis, 2021.

[5] Third World Network, How ‘Digital Trade’ Rules Would Impede Taxation of the Digitalised Economy in the Global South, 2020; Gender & Trade Coalition, Open Letter from the Gender and Trade Coalition to the Director-General and Honorable Delegates of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) ahead of MC12, 2022.

[6] Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN) and Third World Network, International Trade & Investment Rules, Intellectual Property Rights and COVID-19: A perspective from the South, 2021.

[7] Feminists for a People’s Vaccine, International Trade & Investment Rules, Intellectual Property Rights and Covid-19: A Perspective From the South, 2021 and TRIPS Waiver Proposal – An Ongoing Debate, 2021; Feminist COVID-19 Collective, Another World is Possible: A Feminist Monitoring & Advocacy Toolkit for Our Feminist Future, 2020.

[8] World Trade Organization, Draft Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement, 2022.

[9] Third World Network, A global intellectual property waiver is still needed to address the inequities of COVID-19 and future pandemic preparedness, 2022.

INVESTOR-STATE DISPUTE SETTLEMENTS

One of the main frontiers of corporate capture in trade and investment that remains unaddressed is the continued inclusion of investor protection mechanisms in trade and investment agreements. The primary culprit here is the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism, which has historically given unchecked powers to MNCs to sue governments for hundreds of millions of dollars if they suspect a policy measure could hurt their profit margins or investments.[1] In recent years, the injustice, secretiveness, and costs of ISDS cases has brought increased public awareness and opposition towards the mechanism. This has led the EU to attempts and exercises of rebranding ISDS and giving the corporate power grab a friendlier face.[2] This rebranding only addresses some of the worst procedural problems of the ISDS regime while keeping the fundamental injustice of ISDS intact.[3]

Though the number of known ISDS claims appears to be waning, there is a genuine prospect of the fossil fuel industry escalating litigation under ISDS to induce cross-border regulatory chills and generate payouts for stranded assets.[4] Even though the majority of these claims do not result in payouts for claimants, they make it costly for governments to pursue policy actions that threaten MNCs.[5] As more states pursue climate action and other domestic policies, they risk inviting more arbitration from fossil fuel companies.

Fossil fuel companies have to date made extensive use of ISDS, and will likely do so increasingly as assets like foreign-owned coal plants, gas pipelines, and even exploration permits are protected by international investment agreements (IIAs). Around 20% of known ISDS cases are linked to fossil fuel sector investments, with more than two thirds of these cases being won by investors.[6] Of the top 10 largest investment arbitration awards to date, seven have involved fossil fuel companies (ranging from US$1.6 to US$40 billion)—so when these investors win, it is extremely costly for taxpayers and governments.[7]

[1] Feminist Action Nexus for Economic and Climate Justice, A Feminist Agenda for People and Planet: Principles and Recommendations for a Global Feminist Economic Justice Agenda, 2021.

[2] European Commission, Multilateral Investment Court project, n.d.

[3] Public Services International (PSI), The Multilateral Investment Court: The Wolf’s Newest Outfit, n.d.

[4] Tienhaara, Regulatory Chill in a Warming World: The Threat to Climate Policy Posed by Investor-State Dispute Settlement, 2017.

[5] UN Conference on Trade and Development, Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator, 2022.

[6] International institute for sustainable development, Investor-State Disputes in the Fossil Fuel Industry, (2021).

[7] Global Legal Group, International Comparative Legal Guides: Investor-State Arbitration 2022, 2022.

A NEW ERA OF GREEN EXTRACTIVISM

The surge in demand for clean energy and electric vehicles has led to a growing appetite for export-oriented economies in the Global South to extract and export raw minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. These minerals constitute essential components of batteries and other green technologies. The World Bank anticipates that by 2050, the demand for key transition minerals could increase by around 500%.[1]

Despite growing global awareness of the socioecological costs of extractivism, key transition minerals like lithium are increasingly positioned as environmentally benign, and countries in the Global South are encouraged to orient their exports around such minerals.[2] In lithium-abundant resource rich countries like Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile (dubbed the “Lithium Triangle”), lithium expansion will likely drive dispossession of local populations and increase tensions due to resource conflicts—particularly as over 80% of lithium projects are located on Indigenous territories. [3]

[1] World Bank Group, Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition, 2020.

[2] Voskoboynik & Andreucci, Greening extractivism: Environmental discourses and resource governance in the ‘Lithium Triangle’, 2021.

[3] Institute of Development Studies, Bringing Democracy to Governance of Mining for a Just Energy Transition, 2023; Voskoboynik & Andreucci, Greening extractivism: Environmental discourses and resource governance in the ‘Lithium Triangle’, 2021.

Credit: Licadho

LOCAL SITE OF STRUGGLE: GENDERED ACTION IN CAMBODIA’S EXPORT-ORIENTED GARMENT INDUSTRY

Since the 1990s, Cambodia’s export-oriented growth strategy has facilitated the rise of a garment industry dominated by women workers. Facing limited alternatives, women work under the notoriously exploitative conditions of the garment industry and are often hired due to perceptions of their submissiveness, willingness to work for lower wages, and limited knowledge of labor rights.[1]