THE 2024 CRITICAL TRENDS REPORT

This 2024 edition of the Critical Trends Report examines the progress and challenges in realizing the vision of the Feminist Action Nexus for Economic and Climate Justice, as outlined in the Blueprint for Feminist Economic Justice and distilled into our seven key demands.

In this 2024 update, we focus on four thematic areas: 1) debt, 2) the Bretton Woods Institutions (the World Bank and International Monetary Fund), 3) taxation, and 4) climate finance, highlighting key developments and releases of data between late 2023 and October 2024. While this report focuses primarily on global-level advocacy and context trends, we reaffirm our commitment to standing in solidarity with, and amplifying the voices of, those on the frontlines of resistance.

As in 2023, the full Critical Trends Report 2024 is available in four languages: Arabic, French, English and Spanish.

The 2023 flagship Critical Trends Report is available at this link.

THIS IS THE READ MORE

Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus. Donec dui odio, condimentum non venenatis vitae, consectetur nec eros. Fusce a magna feugiat[1] massa scelerisque gravida. Phasellus scelerisque sodales neque sit amet tincidunt. Curabitur convallis mi eu nibh finibus faucibus. Praesent semper vel augue at euismod.

[1] Fourth footnote

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report was written by Arimbi Wahono (Shared Planet), through extensive collaboration with Katie Tobin (Women’s Environment & Development Organization).

We would like to thank the following reviewers for their generous input into and expert review of this report: Sanam Amin, Agatha Canape, Tara Daniels, Guillermina French, Julia Gerlo, Polina Girshova, Sophie Legros, Faith Lumonya, Emilia Reyes, Tove Maria Ryding, Amy McShane, and Shereen Talaat. We envision this continuing project as a contribution to the broader movements for feminist economic and climate justice of which we are part, and are extremely grateful to the colleagues who took the time to strengthen this report and contribute their analysis.

Design by Brevity and Wit. Web platform by Social Ink.

CRITICAL TRENDS IN NUMBERS

51%

of new oil and gas field expansion by 2050 is planned by just 5 countries in the Global North

92%

of the overshoot of the safe fair share of emissions has been caused by rich Global North countries

$2.4 TRILLION

world military expenditure in 2023, after an increase of 9 consecutive years

15.5%

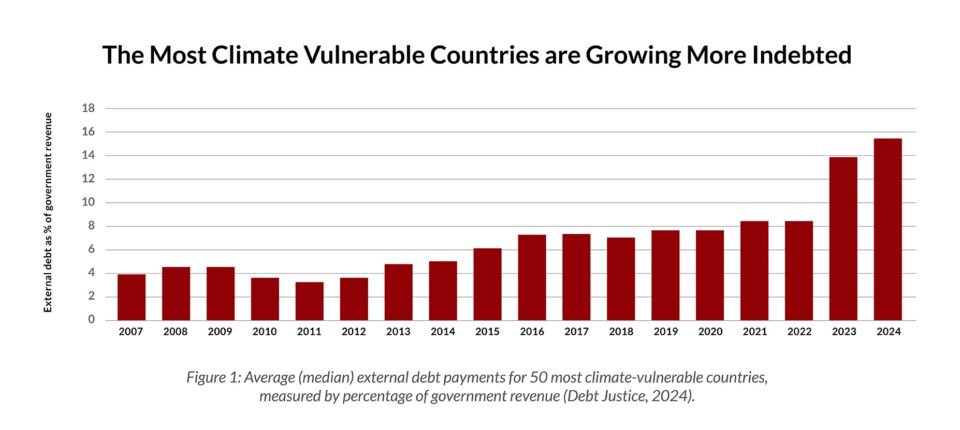

of government revenue (on average) paid to service external debt of the 50 most climate vulnerable countries in 2024

ALMOST HALF

of the world’s population has voted or will be voting in national elections in 2024

45.6%

of World Bank investments in renewable energy in the Global South between 2017 and 2022 threatened land rights through land grabs, displacement, and/or biodiversity loss

INTRODUCTION

In the face of escalating conflict and ecological crises, the need for radical and transformative action on feminist economic and climate justice has never been clearer. The first-ever United Nations (UN) Global Stocktake process in 2023 provided the most comprehensive evaluation of global climate action to date. The conclusion? The world is extremely off track in keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees, and the window of opportunity to act is narrowing.[1] In a year where almost half the world’s population has voted or will be voting in national elections,[2] it is more critical than ever to champion policy platforms that guarantee gender equality, human rights, and the protection of our planet.

[1] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2023) Technical dialogue of the first global stocktake. Synthesis report by the co-facilitators of the technical dialogue.

[2] Mark John and Sumanta Sen (2024) How this year of elections is set to reshape global politics, Reuters.

Global North spends on war and fossil fuels, not climate finance or public services

Rich Global North countries—who have contributed to 92% of the overshoot of the safe fair share of emissions—are disproportionately responsible for driving the climate crisis, but continue to advance fairytales of “green growth” rather than taking responsibility for radical mitigation and reparations for climate action in the Global South.[1] The world’s five largest oil and gas companies made record high payouts to shareholders in 2023,[2] and in the Global North, five countries alone are responsible for 51% of new oil and gas field expansion planned before 2050.[3] At the same time, militarism—which is reaching historic levels of expansion, as illustrated by record highs in defense budgets—is fueling the climate emergency and diverting funds away from climate action and public services.[4]

Nowhere is this more evident than in the Israeli genocide of Palestinians and the expansion of its destruction into Lebanon, backed by US financial and military aid. Decades of Israeli apartheid have left Gaza acutely vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis, particularly as Israel continues to displace Palestinians and systematically attack their public health, environmental, and social infrastructures.[5] The violent occupation has only intensified, with conservative estimates placing Gaza’s death toll at over 180,000 since October 2023, including both direct killings and the devastating effects of Israel’s annihilation of essential infrastructure.[6] This context only magnifies the fundamental role of resistance against occupation and militarism in the struggle for global feminist climate and economic justice.

[1] Jefim Vogel and Jason Hickel (2023) Is green growth happening? An empirical analysis of achieved versus Paris-compliant CO2–GDP decoupling in high-income countries, The Lancet Planetary Health 7(9); Jason Hickel (2020) Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary, The Lancet Planetary Health 4(9).

[2] Global Witness (2024) US & European big oil profits top a quarter of a trillion dollars since the invasion of Ukraine

[3] Oil Change International (2023) Planet Wreckers: How Countries’ Oil and Gas Extraction Plans Risk Locking in Climate Chaos. At the same time, a new report from the Clean Air Fund shows that aid for fossil fuel projects quadrupled in a single year, rising from $1.2bn in 2021 to $5.4bn in 2022: Clean Air Fund (2024) The State of Global Air Quality Funding 2024.

[4] Nan Tian et al. (2024) Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023, SIPRI; Peace and Demilitarization Working Group (n.d.) Addressing Militarism for Climate Action, Women & Gender Constituency.

[5] Climate + Community Project and Grassroots Global Justice Alliance (2024) Climate justice demands ceasefire and arms embargo on Israel; Patrick Bigger et al. (2023) Ceasefire now, ceasefire forever: No climate justice without Palestinian freedom and self‑determination, Climate & Community Institute.

[6] Rasha Khatib, Martin McKee and Salim Yusuf (2024) Counting the dead in Gaza: difficult but essential, The Lancet 404(10449).

A feminist structural lens

Women, girls, and gender-diverse people are acutely impacted not just by conflict and the climate crisis, but by the whole host of macroeconomic factors which constrain the resources countries need to finance gender-just outcomes and climate action. Accessible and affordable public services are the cornerstone of gender equality. Burdened by austerity, women must increase their provision of care work when public services are cut; are more likely than men to be employed in public sector work and so face increased loss of livelihood; and are also generally more likely to be low-income earners that are harmed by cuts to public services and the dismantling of broader gender policies, such as those used to tackle gender-based violence.[1] When their social and economic rights are violated, women also become less able to adapt to climate change and broader ecological destruction.[2]

Gender is systematically constructed by unequal relations of power, access, voice, and rights. A structural feminist analysis therefore demands an understanding of how gender (in)equality informs and is reinforced by political systems, global economic governance, financialization, and militarism.[3] The result of these systems is that structurally marginalized peoples, particularly in the Global South, face disproportionate burdens like loss of livelihood, deteriorating access to essential services, illness, and mortality, all while enduring the continued expropriation of their resources[4] and threats, harassment, and other state-sponsored violence. Power holders in the Global North—multinational corporations, the US Federal Reserve, rich country holders of Global South sovereign debt—have a vested interest in the status quo, which manifests in continued extraction and austerity in the majority world.

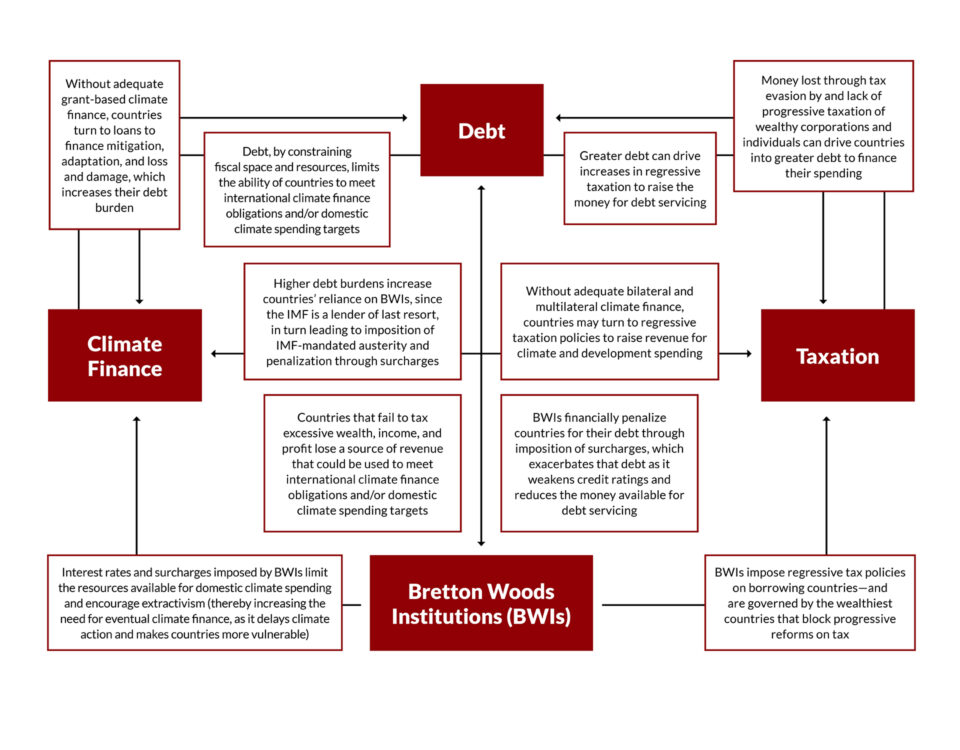

These political and economic developments have profound implications for feminist economic and climate justice, particularly across the four key areas highlighted in this report (debt, tax, the role of the Bretton Woods Institutions, and climate finance). As outlined in the infographic below, both the forces driving trends in these areas and these policy arenas themselves are interconnected, and understanding these interlinkages is key to a structural feminist analysis.

[1] Bhumika Muchhala (2023) A Feminist Social Contract Rooted in Fiscal Justice: An Outline of Eight Feminist Economics Alternatives, ChristianAid.

[2] APWLD, FEMNET, FÓS FEMINISTA and WEDO (2022) Toward a Gender-Transformative Agenda for Climate and Environmental Action.

[3] Bhumika Muchhala (2023) A Feminist Social Contract Rooted in Fiscal Justice: An Outline of Eight Feminist Economics Alternatives, ChristianAid.

[4] Thilagawathi Abi Deivanayaham (2023) Envisioning environmental equity: climate change, health, and racial justice, The Lancet 402(10395).

The interconnectedness of debt, tax, global economic governance under the Bretton Woods institutions (BWIs), and climate finance, as outlined by the structural feminist analysis that informs this report

DEBT

38%

of debt is held by private lenders, who are often the first to profit after delaying negotiations to restructure debt.

4x

increase in debt service as a proportion of government revenue between 2010 and 2024.

ONLY 0.11%

of debt has been relieved through debt swaps globally over the past thirty years

Over the past year, the UN, the World Bank Group, the International Monetary Fund, the G7, and the G20 have all raised the alarm about the worsening debt crisis facing the Global South. Despite consensus on the severity of the crisis, proposed global solutions have not matched the scale of the challenge. While affected states (especially from the Pacific and the African continent) have been vocal about the need to cancel debt, the wealthy countries that hold the majority of Southern debt block any efforts to transform the current creditor-oriented debt resolution regime. In doing so, they actively obstruct gender justice: as debt burdens grow, governments roll back critical public services critical for women and girls, who then make up for the shortfalls through increased provision of care work.[1]

[1] Melania Chiponda and Anne Songole (2023) A Feminist Analysis of the Triple Crisis: Climate Change, Debt, and COVID-19 in Zimbabwe and Kenya, Feminist Action Nexus for Economic and Climate Justice.

AN EVER-WORSENING DEBT CRISIS

In 2024, debt service payments for climate-vulnerable countries approached all-time highs—the worst in at least three decades.[1][2] Climate-vulnerable countries continue to be some of the most critically indebted in the world; as a result, debt servicing is crowding out climate spending, despite the fact that these countries need it the most to adapt to the impacts of climate change. In 2024, the 50 most climate-vulnerable countries averaged external debt payments worth at least 15.5% of their government revenue—four times more than in 2010.[3] Simultaneously, mounting debt pressures governments to finance this debt by expanding the extractive industries that escalate the causes and consequences of biodiversity loss and the climate crisis.[4]

Private lenders (including investment funds, banks, insurance companies, and commodity traders) continue to hold the greatest share (38%) of this debt. Most of these lenders are entities based in the Global North, with 97% of bond claims worldwide being issued under and therefore governed by British or US law.[5] The dominance of private lenders means they are often the first to profit after delaying restructuring negotiations. In critically indebted Suriname, for instance, private creditors reached a deal in November 2023 that allowed them to cancel just $262 million of debt (far below what the IMF deemed necessary for sustainability) in return for a potential $787 million from Suriname’s future oil revenues.[6]

Global South debt is easily aggravated by external economic factors like the interest rates of the wealthy countries that hold their debt, as was the case when US interest rates rose several times throughout 2023, increasing the cost of borrowing for the majority of Southern countries whose debts are largely held in US dollars.[7]

The impacts of interest rate hikes are much worse for countries with weak credit ratings, as they pay out interest rates around 20 points higher than the global benchmark, and over ninefold that of other “developing” countries.[8] Just three agencies (Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch Ratings) control over 90% of global credit ratings, often giving “junk” ratings to poor countries that they deem as riskier investment environments, which forces these countries to pay out higher interest rates on their bonds.[9] In practice, the “Big 3” agencies enforce a vicious cycle in which greater debt can drive weaker credit ratings, in turn increasing the cost of borrowing and exaggerating the burden of debt.[10]

[1] Debt Justice (2024) Debt payments for climate vulnerable countries hit highest level since at least 1990.

[2] More broadly, in the Global South, 130 countries are at least slightly critically indebted. Erlassjahr measures “slightly critical” indebtedness with reference to a country’s level of debt distress according to indicators including public debt as a proportion of annual GDP or government revenues, external debt as a proportion of annual GNI, gdp, or annual export earnings, and external debt service as a proportion of annual export earnings. Slightly critically indebted countries have at least one debt indicator exceeding the lower risk threshold. See Misereor and erlassjahr.de (2024) Global Sovereign Debt Monitor 2024.

[3] Debt Justice (2024) Debt payments for climate vulnerable countries hit highest level since at least 1990

[4] The Centre for Climate Justice, Climate and Community Project, and Third World Network (2024) Exporting Extinction: How the international financial system constrains biodiverse futures

[5] This debt is measured in terms of external interest payments from 49 climate-vulnerable countries from 2023 to 2030. See Debt Justice (2024) Debt payments for climate vulnerable countries hit highest level since at least 1990.

[6] Misereor and erlassjahr.de (2024) Global Sovereign Debt Monitor 2024; Debt Justice (2024) Analysing outcomes from debt restructurings.

[7] Christopher J. Waller (2024) The Dollar’s International Role.

[8] Philip Kenworthy, M. Ayhan Kose, and Nikita Perevalov (2024) A silent debt crisis is engulfing developing economies with weak credit ratings, World Bank Blogs.

[9] Libby George et al. (2024) How Africa’s ‘ticket’ to prosperity fueled a debt bomb, Reuters.

[10] Philip Kenworthy, M. Ayhan Kose, and Nikita Perevalov (2024) A silent debt crisis is engulfing developing economies with weak credit ratings, World Bank Blogs.

FALSE SOLUTIONS DOMINATE DEBT RESOLUTION EFFORTS

The G77 and China bloc of “developing” countries have continued to amplify the longstanding call for a multilateral debt workout mechanism under the auspices of the UN, with all countries negotiating on equal footing. Despite these growing demands, there has been very little action in progressing such a mechanism. Instead, mainstream creditors like the Paris Club and the debt resolution efforts they dominate (like the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments and instruments like debt swaps) continue to advance piecemeal and colonial solutions that prioritize private payouts and obscure the need for debt relief, full cancellation of illegitimate debt, and reparations for the ecological and climate debt that the North owes to the South.

One of the false solutions often peddled by creditors and intermediaries is the use of debt swaps: financial instruments that provide debtors with debt reduction contingent on the newly freed-up resources being spent on specific initiatives. Such solutions are often viewed as an easy win for debtor countries that get to concurrently address their debt and finance critical areas like development, climate, or nature.[1] But evidence shows that debt swaps cannot possibly resolve the scale of the debt crisis: in the past thirty years, debt swaps have treated less than 0.11% of debt. Even if scaled up, debt swaps are slow, complex, and costly instruments with high transaction costs and conditionalities attached. Above all, they distract from the need for unconditional cancellation of debt, while continuing a colonial legacy of Global North countries and their financial intermediaries determining the terms by which the Global South can spend money that is rightfully theirs.[2]

In 2023, Ecuador finalized the world’s largest debt-for-nature swap to date, with the aim of channeling funds into marine conservation in the Galapagos. The Latin American Network for Economic and Social Justice (Latindadd) has criticized the private interest-led deal for its lack of integrity, transparency, and community consultation. Under this deal, Ecuador must cede its sovereignty to accept conditional financing and cover both the costs of a guarantee by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the fees of international private financial and legal advisors, directing funds towards rent-seeking private agents. Rather than delivering positive conservation and community outcomes, the much-touted debt swap has only reinforced exclusion and mismanagement of funds under the guise of equity, while obscuring the need to overhaul the outdated and colonial debt architecture.[3], [4]

[1] Iolanda Fresnillo (2023) Miracle or Mirage? Are debt swaps really a silver bullet?, Eurodad.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Latindadd (2023) Galapagos deal: an ignominious legacy; Latindadd (2024) IDB Investigation Mechanism accepts complaint against Galapagos Debt Swap filed by local communities

[4] For a sense of scale: the debt swap is predicted to channel at least $12 million a year for conservation of the Galapagos Islands, but from 2021-2023 alone Ecuador spent an average $77 million a year on IMF surcharges—the IMF’s penalty for holding “excessive” debt from the Fund—underscoring the ineffectiveness of such debt swaps so long as the broader debt architecture remains untouched. See Ivana Vasic-Lalovic, Michael Galant and Francisco Amsler (2024) A Broader Impact Than Ever Before: An Updated Estimate of the IMF’s Surcharges, CEPR.

Credit: Eranga Jayawardena, AP

DEBT RESTRUCTURING IN ZAMBIA AND SRI LANKA

After over three years of negotiations, in June 2024 Zambia closed its debt restructuring deal under the G20 Common Framework. The deal stipulates that Zambia will pay $450 million this year alone to private bondholders, including asset management firm BlackRock (the largest known holder of external private debt in Zambia and the Global South overall). In the same month, the IMF loaned Zambia $570 million to deal with the country’s worst drought in nearly 60 years. In other words, while the IMF loan recognizes that Zambia requires immediate disbursement of funds, the Common Framework arrangement forces Zambia to use an equivalent of 80% of it to pay back bondholders.[1] If Zambia’s economy does better than expected, it will have to ramp up its debt repayments—but there is no equivalent measure to pause or reduce payments in case of a shock, like the drought it is currently experiencing.[2]

Sri Lanka faces similar terms under its restructuring deal reached in July 2024 (negotiated outside the G20 Common Framework, for which it was ineligible due to being a middle-income country). Under these terms, Sri Lanka will repay bondholders 46% more than government lenders if the economy performs better than expected, following an established trend of private creditors being paid first while losing less compared to bilateral creditors.[3] As a proportion of government revenue, Sri Lanka will be paying twice as much as Zambia, with over 25% of government revenue being siphoned off to external debt payments for at least the next decade.[4]

[1] Monique Vanek (2024) Zambia Gets $570 Million From IMF as Drought Takes Toll, Bloomberg UK.

[2] Debt Justice UK (2024) Zambia’s debt relief deal with bondholders, initial analysis.

[3] Matthias Schlegl, Christoph Trebesh, and Mark L. J. Wright (2019) The Seniority Structure of Sovereign Debt, National Bureau of Economic Research.

[4] Debt Justice (2024) Sri Lanka’s bondholders to get repaid 20%-45% more than governments.

THE ROLE OF THE BRETTON WOODS INSTITUTIONS

80

years of global economic hegemony governed by the undemocratic IMF and World Bank

2

gender commitments in IDA21 (reduced from 8).

13

heavily indebted countries will still have to pay IMF surcharges in 2026, on top of regular interest on their loans.

The year 2024 marks the 80th anniversary of the establishment of the World Bank and IMF. At a time of urgent need for democratic, accountable, and equitable global governance, these institutions continue to demonstrate that they are fundamentally incompatible with such objectives. The BWIs’ governance structures remain dominated by the Global North, and their treatment of debt-ridden countries in the South perpetuates cycles of punishment, deepening both austerity and the climate crisis. The growing involvement of these institutions in both the climate and gender arenas is no cause for celebration. Instead, it serves to mask the harm they inflict on people and the planet, while actively limiting meaningful civic engagement, including by co-opting and diluting radical visions on gender, climate, and development.[1]

[1] Rachel Nadelman (2024) Is the World Bank rolling back commitments to citizen engagement, again?, Bretton Woods Project.

THE WORLD BANK GROUP CONTINUES TO PRIORITIZE PRIVATE INVESTMENT

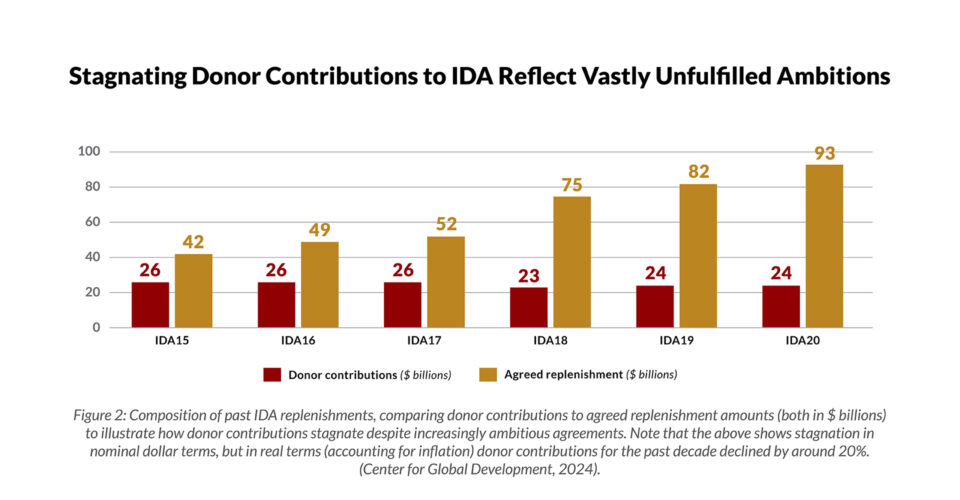

The upcoming 21st replenishment (IDA21) of the International Development Association (IDA) is a crucial opportunity to deliver the resources for gender-just public services and climate action in the poorest countries. A World Bank financing arm, IDA is the largest multilateral provider of grants and concessional (i.e., cheaper than market rate) finance for low-income countries.[1] World Bank President Ajay Banga has urged wealthy countries to make this replenishment cycle (due to be completed in December 2024) “the largest of all time”[2] by providing at least $28-30 billion, a nearly 10% increase in real terms from IDA20. Over the past decade, however, donor countries’ contributions have declined by around 20%, and in 2024, large donors have already signaled their unwillingness to maintain existing contributions, let alone increase them.[3]

Banga’s promises of reform have manifested as a drive for streamlining and simplification that has made IDA21 much less ambitious than IDA20 in terms of gender,[5] demonstrating the superficiality of the recently released World Bank Group Gender Strategy 2024-2030.[6] According to analysis from the Center for Global Development, IDA21 has not only reduced the number of gender policy commitments from eight to a paltry two, but it also restricts these already diminished targets to only 18 of the most vulnerable IDA countries—just 25% of all IDA countries.[7] Meanwhile, stagnating or declining IDA financing means that the World Bank and its rich donor countries refuse to come up with the money that is necessary to materially advance gender-just outcomes.

Just as important as the amount pledged towards IDA21 is the recipient of that funding.[8] In line with the Bank’s “private finance-first” development model—where public funds are used to attract private investment, reducing risk for private enterprises through public subsidies—the Bank launched the IDA Private Sector Window (PSW) in 2017.[9] Instead of providing resources directly to governments, the PSW eats into scarce public IDA resources to “catalyze” private investment through the Bank’s private sector arms. As a result, one of those arms (the International Finance Corporation, or IFC) has since become a net recipient of—rather than a contributor to—IDA resources.[10] Despite receiving billions in IDA financing, the PSW has been unable to reverse the downward slide in IFC commitments to countries most in need, while IFC projects in those countries are performing worse than ever in terms of development impacts (per the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group Assessment).[11]

[1] Development Finance Vice Presidency of the World Bank Group (2024) International Development Association.

[2] Ajay Banga (2023) Remarks by Ajay Banga at the International Development Association (IDA) Midterm Review, World Bank Group.

[3] Clemence Landers (2024) Can IDA Break the 100-Billion-Dollar Mark? The Math Is Difficult, but Not Impossible, Center for Global Development.

[5] Mary Borrowman and Kelsey Harris (2024) Streamlining Versus Substance: Risks and Opportunities for Gender Equality in the IDA21 Replenishment, Center for Global Development.

[6] World Bank Group (2024) World Bank Gender Strategy 2024 – 2030: Accelerate Gender Equality to End Poverty on a Livable Planet.

[7] Mary Borrowman and Kelsey Harris (2024) Streamlining Versus Substance: Risks and Opportunities for Gender Equality in the IDA21 Replenishment, Center for Global Development.

[8] Jayati Ghosh and Farwa Sial (2021) A Wrong Turn for World Bank Concessional Lending, Project Syndicate.

[9] World Bank Group (2015) From billions to trillions : MDB contributions to financing for development; International Development Association (2024) What is the IDA Private Sector Window?, World Bank Group.

[10] Charles Kenny (2019) Is the New Model IFC a Good Deal for IDA Countries?, Center for Global Development.

[11] Charles Kenny (2024) Has the IDA PSW Increased IFC Investments in IDA Countries?, Center for Global Development; World Bank Group (2023) Results and Performance of the World Bank Group 2023, Independent Evaluation Group.

…WHILE THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND OVERCHARGES ITS DEBTORS

The IMF’s regressive surcharge policy punishes countries for indebtedness at exactly the times they can least afford it, imposing penalties on countries with large loans that are not paid back within a short timeframe.[1] Countries paying surcharges on top of an already crushing debt burden include climate-vulnerable Pakistan—currently facing historic loss and damage due to floods—and Egypt, which has experienced worsening poverty and a hunger crisis, fueled by the IMF-backed austerity measures of the last decade.[2] Prior to the 2024 surcharge review, Pakistan and Egypt were set to pay $445 million and $646 million in surcharges respectively from 2024 to 2028.[3]

Overall, indebted countries had been estimated to pay a cumulative $10 billion in surcharges from 2024 to 2028, all while the IMF was well ahead of its fundraising targets.[4] The staggering revenue derived from surcharges can prolong and worsen economic downturns—exactly the opposite of what the IMF purports to achieve.[5] In a positive turn of events, persistent civil society campaigning and global pressure drove the IMF to lower its surcharges by 36% in October 2024. In 2026, it is expected that the number of surcharge-paying countries will fall to 13 (down from 22 countries in 2024, but still more than the pre-pandemic figure of 8 countries in 2019).[6] Many civil society organizations maintain that incremental changes are insufficient, reiterating the demand for surcharges to be eliminated.[7]

Also drawing scrutiny is the IMF’s May 2024 interim review of the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST),[8] which praises the “usefulness” of the RST while ignoring civil society concerns on greenwashing, austerity, and its role in exacerbating debt.[9] Financed through Special Drawing Rights (SDRs, an IMF reserve currency used to boost liquidity), the RST requires borrowing countries to implement “permanent institutional changes” to “help attract private investors.” To gain access to the RST, borrowers need to have an existing IMF program in place—which in many cases includes conditionalities that contradict the climate-related aims of the RST.[10] In Senegal, for instance, an RST arrangement aimed at mitigation clashes with another IMF program promoting fossil fuel expansion.[11] The setup of the RST as a debt-creating instrument (while SDR allocations to rich countries add to their reserves without increasing their debt) underscores the coloniality of IMF financing mechanisms: the Northern-dominated IMF offers only a meager sum for much-needed climate action to the Global South countries that need it most, and refuses to deliver the resources unless extractivist or austerity-driving conditionalities are met.

Against a shared backdrop of punitive imposition of austerity and unambitious efforts to drive climate action, the IMF’s Interim Guidance Note on Gender (released in 2024) appears both massively insufficient and symbolic.[12] In it, the IMF outlines voluntary guidance on how staff can incorporate a gender analysis into IMF activities, while uncritically promoting policy solutions like public-private partnerships and private finance. Absent from all of this work is an acknowledgement of historical and ongoing harm to women and gender-diverse people in particular caused by these policies—and by the IMF itself.[13]

[1] Joseph E. Stiglitz and Kevin P. Gallagher (2022) Understanding the consequences of IMF surcharges: the need for reform, Review of Keynesian Economics 10(3).

[2] MENAFem Movement for Economic Development and Ecological Justice (2024) End surcharges campaign; Ruth Michaelson and Menna Farouk (2023) Inflation, IMF austerity and grandiose military plans edge more Egyptians into poverty, The Guardian; Ivana Vasic-Lalovic, Michael Galant, and Francisco Amsler (2024) A Broader Impact Than Ever Before: An Updated Estimate of the IMF’s Surcharges, CEPR; Human Rights Watch (2023) Egypt: IMF Bailout Highlights Risks of Austerity, Corruption.

[3] Ivana Vasic-Lalovic, Michael Galant, and Francisco Amsler (2024) A Broader Impact Than Ever Before: An Updated Estimate of the IMF’s Surcharges, CEPR; Timothy E. Kaldas (2024) Economics is political: the IMF’s programme in Egypt can’t succeed without reforming both, The Bretton Woods Project.

[4] Ibid.

[5] MENAFem Movement for Economic Development and Ecological Justice (2024) End surcharges campaign; Shereen Talaat and Dan Beeton (2024) Now would be a good time for the IMF to do away with unfair and unnecessary surcharges, MENAFem Movement for Economic Development and Ecological Justice.

[6] International Monetary Fund (2024) Frequently Asked Questions on the Fund’s Charges and the Surcharge Policy.

[7] Bretton Woods Project (2024) IMF surcharges review: tinkering at the margins as crises deepen?.

[8] For more on SDRs, see the 2023 Trends Report and Bretton Woods Project (2024) IMF board’s reluctance leaves Special Drawing Rights as an underused tool in Fund’s toolbox.

[9] Jwala Rambarran (2024) Making Sense of the IMF’s Interim Review of the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, Global Development Policy Center; International Monetary Fund (2024) Interim Review of The Resilience and Sustainability Trust and Review of Adequacy of Resources.

[10] International Monetary Fund (2023) Resilience and Sustainability Facility—Operational Guidance Note.

[11] Recourse (2024) Report on IMF Resilience and Sustainability Trust – Recourse.

[12] International Monetary Fund (2024) Interim Guidance Note on Mainstreaming Gender at The IMF.

[13] Bretton Woods Project (2024) IMF’s Interim Guidance Note on Mainstreaming Gender fails to address negative gendered impacts of IMF austerity.

Credit: Agustin Marcarian, Reuters

THE IMF AND WORLD BANK’S PUSH FOR AUSTERITY IN ARGENTINA

Argentina is the IMF’s largest debtor, owing $42.9 billion in debt in 2024 and slated to pay billions in surcharges over the next few years.[1] In 2021, the IMF rejected Argentina’s request for temporary relief from surcharges, forcing the country into a cycle of short-termist extractivism to finance its unsustainable debt burden.[2] Since then, Argentina has negotiated several deals with the IMF that have involved expanding export revenues through soy, mining, and fossil fuels—sectors notorious for driving deforestation and biodiversity loss and threatening Indigenous rights and livelihoods.[3] The Fund has encouraged the continued exploitation of the Vaca Muerta Formation to boost oil and gas exports, projecting that Argentina could increase its exports from 100,000 to 900,000 barrels per day from 2023 to 2030.[4] In its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP), the Argentinian government identifies its debt as a major barrier to achieving crucial conservation targets.[5]

In late 2023, Argentina elected radical free market capitalist and ultra right-wing climate denier Javier Milei as president—a move both the Bank and the Fund have celebrated.[6] The IMF commended Milei for “taking bold actions to restore macroeconomic stability and begin[ning] to address long-standing impediments to growth.”[7] How has he done it? Milei has dissolved the environment ministry, taken an ax to pensions and universities, fired thousands of public sector workers, made plans to privatize more than two dozen state-owned companies providing critical public services,[8] and slashed an array of gender-responsive services and policies—including those set aside for protecting victims of femicides, violence, and trafficking, as well as broader care and social protection services.[9]

[1] International Monetary Fund (2024) Total IMF Credit Outstanding Movement From October 01, 2024 to October 29, 2024

[2] Jorgelina Do Rosario and Eric Martin (2021) IMF Rejected Argentina’s Request for Temporary Surcharges Relief, Bloomberg UK.

[3] The Centre for Climate Justice, Climate and Community Project, and Third World Network (2024) Exporting Extinction: How the international financial system constrains biodiverse futures

[4] FARN (2024) Argentina under IMF Orthodox Adjustment Policy; International Monetary Fund (2024) Argentina: Seventh Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility; Recourse and Periodistas por el Planeta (2024) The IMF talks about climate change but pushes Argentina into fracking.

[5] The Centre for Climate Justice, Climate and Community Project, and Third World Network (2024) Exporting Extinction: How the international financial system constrains biodiverse futures.

[6] The World Bank Group (2024) Argentina Overview: Development news, research, data.

[7] International Monetary Fund (2024) Argentina: Seventh Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility.

[8] Robert Plummer (2024) Have Milei’s first six months improved the Argentine economy?, BBC News; FARN (2024) Argentina under IMF Orthodox Adjustment Policy.

[9] FARN, ETFE, and Recourse (2024) State of affairs in Argentina and the IMF agreement: views from civil society; Civil Association for Equality and Justice (2024) Un ajuste que agranda la brecha.

TAXATION

$5 TRILLION

in potential tax revenues to be lost to tax havens over the next decade.

110

countries voted to approve the Terms of Reference for a new UN Framework Convention on International Taxation.

$190 MILLION

of potential tax revenue in Kenya is lost to global tax abuse annually.

Over the next decade, multinational corporations and wealthy individuals will appropriate nearly $5 trillion in tax revenues by exploiting tax havens.[1] While corporate profits soar, corporate tax revenues remain stagnant.[2] To make up for the shortfalls in income and corporate tax, governments often turn to regressive taxation like consumption taxes that disproportionately burden women, who constitute a greater proportion of low-income earners than men. Transforming the global tax regime is one element of the systems change required for feminist climate and economic justice: first to enable governments to raise much-needed revenue for climate action and gender-responsive public goods and services, and more broadly to repair and rebalance historical inequalities including along lines of gender.[3]

[1] Tax Justice Network (2023) The State of Tax Justice 2023.

[2] Joseph E. Stiglitz (2024) The International Tax System Is Broken, Foreign Affairs.

[3] Global Tax Justice (2021) Feminist Taxation Framing: with examples from Uganda. For more on the connections between tax, gender, and environmental justice, see the forthcoming brief authored by Arimbi Wahono (Shared Planet) for WEDO, the Financial Transparency Coalition, and the Center for Economic and Social Rights.

REFORMING THE GLOBAL TAX REGIME

Countries of the Global South, led by the Africa Group, have led a long and persistent campaign for a legally binding UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation. 2023 was a breakthrough year, as the UN General Assembly approved a resolution to begin work on such a convention, to make the global tax regime more equitable by grounding it in the more democratic, multilateral forum of the UN and closing existing loopholes on tax avoidance and corporate tax abuse.[1]

Negotiations over the Convention in mid-2024 were fraught with contest from rich countries seeking to preserve the current OECD-dominated global tax regime—where they have much more power to shape the rules in their favor. Nevertheless, under the one-country, one-vote system at the UN, a historic UN decision ruled to negotiate a UN Tax Convention and two further protocols (legally binding instruments to implement the convention), with a deadline of 2027. 110 countries voted for the decision—a landslide—while just eight countries voted against the final Terms of Reference (ToR). All eight were wealthy, OECD countries: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, Israel, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand (EU countries shifted their vote from against to abstain).[2]

Civil society actors have praised the final ToR for being a “beacon of hope for a fair and efficient global tax system,” including clear commitments to address tax dodging while drawing explicit links between tax and environmental protection.[4] Global South governments were instrumental in driving the ambitiousness of the text. Latin America pushed for the ToR to recognize the convention’s role in reducing inequality by making the ultra-rich pay their fair share in taxes.[5] Brazil advocated for “progressive” to be added as an objective of the convention (which it also supported throughout the year in its capacity as G20 President), but objections from Canada, Estonia, and Saudi Arabia resulted in this being left out—though other principles on inclusivity, fairness, and transparency made it into the text.[6]

Gender is starkly missing from the ToR, however, despite its explicit mention in the original resolution put forward by the Africa Group in 2023.[7] Civil society actors including the Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development (APMDD) fought to bring it back at this year’s negotiations, but their calls went unanswered—making it ever more critical to amplify demands for explicit recognition of the impacts that tax systems have on gender equality in future negotiations.[8]

[1] United Nations (2023) Second Committee Approves Nine Draft Resolutions, Including Texts on International Tax Cooperation, External Debt, Global Climate, Poverty Eradication.

[2] Tove Ryding (2024) After landslide vote, UN adopts ambitious mandate for three legally binding global tax deals, Eurodad.

[4] Tove Ryding (2024) After landslide vote, UN adopts ambitious mandate for three legally binding global tax deals, Eurodad.

[5] Tove Ryding (2024) UN Tax Convention negotiations: New draft text shows that an ambitious outcome is still within reach, Eurodad.

[6] Tove Ryding (@toveryding) (2024) Post from 16 Aug 2024, X; G20 (2024) At the G20, Brazil’s proposal to tax the super-rich may raise up to 250 billion dollars a year.

[7] United Nations General Assembly (2023) Promotion of inclusive and effective international tax cooperation at the United Nations.

[8] Civil Society Financing for Development Mechanism (2024) The Preamble and Principles: A Place for Human Rights, The FfD Chronicle.

Credit: Getty

KENYA’S GEN Z REJECT IMF-BACKED TAX PROPOSALS IN MASS PROTESTS

In May 2024, Kenya’s Parliament announced a Finance Bill proposing tax increases on a range of essential goods and services (including bread, vegetable oil, sanitary pads, and diapers), in order to raise the funds needed to pay back the $80 billion Kenya owes its creditors. As part of Kenya’s IMF program, the Fund has made its lending contingent on the government reducing its budget deficit—including by introducing regressive taxes that the IMF understood would risk sparking popular protest because of its impacts on the country’s poorest.[1] When the Finance Bill was announced, the IMF praised the government for driving the public expenditure cuts deemed necessary for “fiscal stability.”[2]

In response, Kenyan youth rapidly mobilized on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram to call for peaceful protests.[3] Within just two weeks of protest, the state’s brutal crackdown resulted in at least 39 deaths, 361 injuries, 627 arrests, and 32 cases of enforced or involuntary disappearances, with many other protesters forced into hiding.[4] In the face of mounting pressure, President William Ruto rejected the bill shortly after demonstrations began (resulting in credit ratings agency Moody’s downgrading Kenya into “junk” territory, making it more expensive for Kenya to access international capital).[5] Yet protests have continued, with calls for Ruto’s resignation growing louder.[6] The protests have been unique in their explicit rejection of the IMF’s involvement in fueling the debt crisis that led to the Finance Bill. Young protesters brandished signs that declared “We ain’t IMF bitches” and “Kenya is not IMF’s lab rat,” while labeling Ruto as a “puppet” of the IMF.[7]

The country’s debt burdens are indeed severe: Kenya’s debt is 73% of its GDP.[8] Payments on debt interest alone exceed combined spending on education, childhood nutrition, clean drinking water, and health,[9] reflecting a wider trend in Africa where debt service exceeds public spending on services required to fulfill human rights and ensure ecological integrity.[10] Though Kenya loses $190 million annually to global tax abuse,[11] Ruto’s government chose to raise taxes on consumption required for survival instead of on corporations and wealthy individuals.[12] Kenya’s case illustrates how injustices in debt, tax, and IMF-imposed austerity all intersect to deepen economic inequality—but also to fuel popular resistance against both global financial control and the government policy beholden to it.[13]

[1] International Monetary Fund (2024) Kenya: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Sixth Reviews Under the Extended Fund Facility and Extended Credit Facility Arrangements; erlassjahr.de (2024) #RejectFinanceBill2024 protests in Kenya – When austerity leads to human rights violations; Government of Kenya (2024) Finance Bill, 2024; Basillioh Rukanga (2024) What are Kenya’s controversial tax proposals?, BBC News.

[2] International Monetary Fund (2024) IMF Reaches Staff-Level Agreement with Kenya on Seventh Reviews of the Extended Fund Facility and Extended Credit Facility Arrangements and the Second Review Under the Resilience and Sustainability Facility.

[3] Wycliffe Muia (2024) Kenya Finance Bill: Gen Z anti-tax revolutionaries – the new faces of protest, BBC News.

[4] Daniel Mule (2024) Update on the Status of Human Rights in Kenya during the Anti-Finance Bill Protests, Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.

[5] Libby George et al. (2024) How Africa’s ‘ticket’ to prosperity fueled a debt bomb, Reuters.

[6] Giulia Paravicini and Aaron Ross (2024) Kenya president backs down on tax hikes after deadly unrest, Reuters.

[7] Andres Schipani and Aanu Adeoye (2024) Kenya’s mass protests expose African fury with IMF. See also Wangari Kinoti and Lina Moraa (2024) Kenya’s growing youth movement for fiscal justice rejects IMF-mandated austerity, Bretton Woods Project.

[8] International Monetary Fund (2024) General government gross debt as percent of GDP.

[9] James Thuo Gathii (2024) Alternatives to Kenya’s Austerity and the Militarized Response to the GenZ Revolution, AfronomicsLaw; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2024) A world of debt: Global debt vulnerabilities and their impact on developing countries.

[10] Debt Service Watch (2023) The Worst Ever Global Debt Crisis.

[11] Tax Justice Network (n.d.) Country Profiles: Kenya.

[12] James Thuo Gathii (2024) Alternatives to Kenya’s Austerity and the Militarized Response to the GenZ Revolution, AfronomicsLaw.

[13] For more on this, see Melania Chiponda and Anne Songole (2023) A Feminist Analysis of the Triple Crisis: Climate Change, Debt, and COVID-19 in Zimbabwe and Kenya, Feminist Action Nexus for Economic and Climate Justice.

CLIMATE FINANCE

$28-35 BILLION

in grant-equivalent climate finance mobilized in 2022, far short of the $100 billion commitment (itself insufficient).

42x

projected increase in demand for lithium by 2040, driven by an increasing appetite in the North for electric vehicles.

$700 MILLION

pledged so far to the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage – nowhere near enough.

Global North, or “developed,” countries are obligated under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Paris Agreement to provide climate finance to “developing” countries. This finance is essential to address the climate crisis, particularly since the Global South is disproportionately impacted not just by climate change and ecological debt, but also by austerity and a sovereign debt crisis. Yet, wealthy countries consistently fail to deliver adequate, public, and grant-based finance for mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage, despite modest targets. This negatively impacts the women, girls, and gender-diverse people who have the least resources and take on increased care burdens in the face of a climate crisis, all while remaining at the forefront of resisting the extractive systems driving this crisis.

FROM $100 BILLION TO A MEANINGFUL—AND ACHIEVABLE—GOAL?

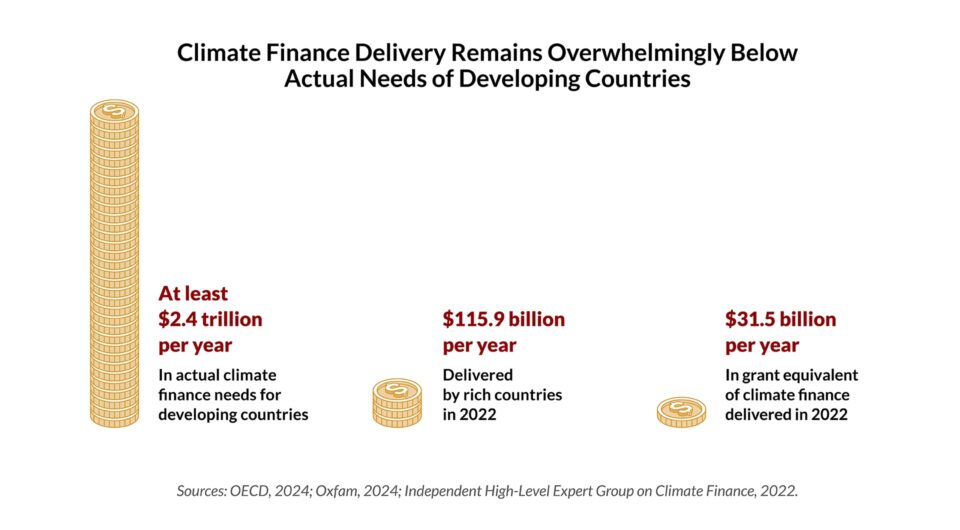

In 2024, the OECD announced that developed countries had finally met, for only 2022, their annual commitment under the UNFCCC to provide $100 billion in climate finance to developing countries. Their numbers indicate that $115.9 billion was provided and mobilized in 2022, up 30% from 2021.[1] A closer look by Oxfam shows that a significant portion (69%) of the public climate finance provided came in the form of loans; when accounting for the grant equivalent of this finance, developed countries provided only $28-35 billion in 2022, of which a vastly inadequate $12.5-15 billion was allocated towards climate adaptation.[2] Much of this funding has gone towards projects that do not seem to fund either mitigation or adaptation, including Japan financing a new coal plant in Bangladesh and the United States offering loans to Haiti for a hotel expansion.[3]

Illustrating the increasingly private-led approach to climate finance, the OECD has highlighted that “the private sector will be key to further bridging the investment gap.”[5] This approach undermines meaningful climate justice by diverting scarce public resources—which could be used for gender-responsive services or locally-led adaptation—towards subsidizing private returns through “market opportunities.”[6] According to OECD reporting, private finance mobilized (subsidized) by public climate finance was $21.9 billion in 2022.[7]

Climate finance also risks being diverted to “green” projects that are just as extractivist and exploitative as their fossil fuel predecessors. This prospect is especially alarming with projected demands for critical raw materials—for one, lithium demand is expected to increase 42 times by 2040, driven by an increasing appetite in the North for electric vehicles.[8] The land defenders risking their lives to protect the environment often face both lethal and non-lethal attacks from government and industry forces attempting to silence them, with women in particular facing sexual violence and other gender-specific harm including community rejection.[9]

The new annual climate finance goal under the UNFCCC, to be set by 2025, presents an important opportunity to address the real needs of developing countries—in the trillions of dollars per year—through the delivery of new, additional, public, and grant-based climate finance, while reinforcing the responsibility of wealthy countries to fund these efforts.[10] Civil society is advocating for qualitative standards and indicators to ensure that climate finance contributes to the promotion and protection of human rights and is steered towards effective solutions—not false ones that prioritize profits or place a green guise over extractivism.

[1] OECD (2024) Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022.

[2] Jan Kowalzig et al. (2024) Climate Finance Short-Changed, 2024 Update, Oxfam.

[3] Emma Rumney et al. (2023) Special Report: Nations who pledged to fight climate change are sending money to strange places, Reuters.

[5] OECD (2024) Developed countries materially surpassed their USD 100 billion climate finance commitment in 2022.

[6] Nick Buxton et al. (2024) Energy, Power and Transition: State of Power 2024, Transnational Institute.

[7] OECD (2024) Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022.

[8] Julia Gerlo and Marius Troost (2023) The foreign financiers of Argentina’s lithium rush, Both Ends.

[9] Global Witness (2023) Standing firm: The Land and Environmental Defenders on the frontlines of the climate crisis; Ana Fornaro and María Eugenia Ludueña (2023) Indigenous women lead battle for land rights in Argentina, OpenDemocracy; Merlyn Thomas and Lara El Gibaly (2024) Neom: Saudi forces ‘told to kill’ to clear land for eco-city, BBC News.

[10] ActionAid International (2024) Finding the Finance: Tax Justice and the Climate Crisis.

MULTILATERAL CLIMATE FUNDS

The three multilateral climate funds serving the UNFCCC (the Adaptation Fund, the Global Environment Facility, and the Green Climate Fund, or GCF) remain significantly underfunded. The Adaptation Fund continues to fall short of its resource mobilization targets,[1] and the GCF’s second replenishment of $12.8 billion for 2024-2027, though higher than the $10 billion in the first replenishment period (2019-2023), offers little to no real increase when considering inflation.[2] Meanwhile, the newly established Fund for responding to Loss and Damage (FrLD) remains under intense civil society scrutiny, particularly due to its severe underfunding (with only $700 million pledged) and the decision to appoint the World Bank as interim host.[3]

Communities in need of climate finance remain concerned that climate funds are neither sufficient nor equitably accessible due to the complex, bureaucratic processes necessary to access these funds, such as stringent reporting requirements.[4] As a result, civil society advocacy has emphasized the need for a community access window within the FrLD to facilitate direct access for frontline communities.[5] Most important is the demand for greater (public) financing and ambition, not just piecemeal reforms to “improve access” without significant scale-up in the resources committed to the major multilateral climate funds.

[1] Adaptation Fund Board (2024) Update on Resource Mobilization for the Fund.

[2] Green Climate Fund (2024) GCF-2 – Resource mobilisation.

[3] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2024) Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-eighth session, held in the United Arab Emirates from 30 November to 13 December 2023. Part one: Proceedings.

[4] The Climate Reality Project Philippines (2024) Statement on the Philippines’ selection to host the Loss and Damage Fund Board.

[5] The Loss & Damage Collaboration (2024) Open Letter to the Board of the Loss and Damage Fund on Direct Community Access.

Credit: IMF-WB Out of Recovery Campaign

THE WORLD BANK’S PUSH TO PRIVATIZE THE LOW-CARBON TRANSITION

The World Bank advances free-market policies (like privatization, financial liberalization, and trade liberalization) in the Global South through conditional lending, particularly in times of economic crisis. As the Bank becomes more involved in delivering climate finance, it continues this pattern by imposing neoliberal reforms in countries’ energy sectors as conditions for receiving funds. A recent report by the Bretton Woods Project highlights how the Bank’s Development Policy Financing (DPF) plays a crucial role in pushing for neoliberal energy sector reform by increasing private sector involvement.[1]

In the Philippines, Development Policy Loans (DPLs) for 2020-2023 totaling $4.85 billion were tied to 59 binding conditions for neoliberal reforms, including the full liberalization of the renewable energy sector (including by allowing foreign majority ownership) and regulation to create a market for electric vehicles. Analysis by IBON International revealed that the DPLs provided to the Philippines exacerbated systemic violence against women through resource plunder, labor exploitation, militarization, and state repression, all while deepening the country’s debt burden.[2]

This is part of a broader trend: between 2017 and 2022, 45.6% of the Bank’s investments in renewable energy across the Global South were found to have “potential impacts on land rights,” including land grabs, the displacement of local communities, and damage to biodiversity and other natural resources.[3] When displacement occurs, women often face greater challenges than men, particularly in accessing remunerative work in resettlement areas.[4]

[1] Jon Sward and Laure-Alizée Le Lannou (2024) Gambling with the planet’s future? World Bank Development Policy Finance, ‘green’ conditionality, and the push for a private-led energy transition, Bretton Woods Project.

[2] IBON International (2024) Reproducing systemic violence against women: Risks of World Bank’s Development Policy Loans to women’s rights in the Philippines.

[3] Mark Moreno Pascual (2023) Lost in Transition: Analysis of the World Bank’s Renewable Energy Investments since Paris, Recourse.

[4] Fadzilah Majid Cooke et al. (2017) The Limits of Social Protection: The Case of Hydropower Dams and Indigenous Peoples’ Land, Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 4(3).

CONCLUSION

Worsening global economic and environmental crises demand bold action on feminist economic and climate justice. Incremental reforms, feel-good rhetoric, and false, technocratic, market-based solutions all fall woefully short of addressing the systemic crises we face.

More than ever, we need a reinvigorated multilateral system that champions strategic structural transformations on debt, climate finance, global economic governance, and tax. At the international level, civil society has many opportunities ahead to advance this vision, including:

- Continued negotiations over the UN Framework Convention on Tax and the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage;

- The setting of the NCQG on climate finance;

- The process towards the UN Financing for Development conference in July 2025, a critical avenue for equitable negotiations on reforming the international architecture on debt, tax, and global economic governance.

While this paper focuses primarily on global-level advocacy, a feminist structural analysis centers people’s movements and rights defenders everywhere in their work to build economies of solidarity and reciprocity; protect their land and their rights from austerity, extractivism, and militarism; and envision a collective future where economic, ecological, and gender justice prevail. Sustained by radical imagination for a better world, it is that work that drives us forward.